Headlines in recent weeks have been dominated by the meeting between President Cyril Ramaphosa and Donald Trump, after the US president granted asylum to white South African farmers.

Framed by Trump as a response to alleged land seizures and violence, the move has been widely criticised as a politically motivated gesture aimed at energising his conservative base ahead of the US mid-term elections. This culminated in a televised version of what Trump might conceive of as version two of The Apprentice in the Oval Office. Despite the ambush, the South African delegation held its ground and demonstrated that white farmers are hardly at disproportionate risk in the country. Many find Trump’s politicking distasteful in the context of having essentially characterised other asylum-seekers to the US as criminals or illegal migrants.

As much as Trump’s reality-TV delusions persist, this moment presents an opportunity for introspection, given South Africa’s own challenges with immigration. While the United States faces scrutiny for the politicisation of asylum, South African politicians have similarly weaponised migration to serve populist agendas. South Africa stands at the centre of intricate migration dynamics that continue to shape its socio-economic landscape, development trajectory, and national security concerns. As one of the continent’s most industrialised economies, South Africa has long been a destination for migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees from across Africa.

In a bid to intensify efforts against illegal immigration, Home Affairs Minister Leon Schreiber recently launched Operation New Broom, a nationwide, technology-driven initiative aimed at identifying, arresting and deporting undocumented foreign nationals, particularly those occupying public spaces. The operation is supported by biometric verification systems, which help detect fraudulent documents and verify a person’s immigration status. This initiative forms part of a broader strategy to clamp down on illegal migration through the use of real-time data and enhanced border control mechanisms.

A substantial proportion of migrants cross the border without any documentation. The majority originate from Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Malawi, Lesotho and Nigeria. These migration flows were and are still driven by multiple push and pull factors, including economic hardship, civil unrest and environmental changes in migrants’ home countries. As climate change, organised crime and extremist activity intensifies in some areas, internal displacement and cross-border migration into South Africa are expected to increase, further complicating the country’s migration governance.

In an attempt to curb the influx, the South African government erected electric fences along its borders with Zimbabwe and Mozambique. This was inefficient; illegal migrants continue to enter illegally by damaging the fence. The establishment of the Border Management Authority (BMA) has augmented the fencing efforts. The BMA’s mandate is to manage and secure South Africa’s borders. This includes facilitating legitimate movement of people and goods while preventing and mitigating illegal activities at ports of entry and within the border law enforcement area. In the 2024–25 festive season, the BMA recorded a 215% increase in the prevention of illegal border crossings, intercepting more than 50 000 undocumented people, a sharp rise from 15 924 in the previous year.

Despite the deployment of drones, surveillance equipment and improved patrols, South Africa’s border security continues to be problematic. The BMA and the police have both acknowledged ongoing issues, including infrastructural decay and systemic corruption among border officials, which compromise the integrity of enforcement efforts.

The government has, since the democratic transition, enacted legislation intended to manage migration more effectively. The White Paper on International Migration (1999) laid the foundational policy vision, highlighting the importance of balancing national interests with human rights obligations. The Refugees Act of 1998 and the Immigration Act of 2002, later amended in 2004 and 2007, were designed to regulate the entry and residence of foreign nationals, establish procedures for asylum, and address irregular migration. Yet, implementation has often lagged behind legislative intent. There is a discernible disconnect between policy and practice, particularly with regard to consistent border control and fair refugee processing systems.

There is no definitive method to accurately determine the number of undocumented migrants in South Africa. Estimates vary widely and are often politicised. This is not unique to South Africa — globally, countries struggle to account for their undocumented populations because of the clandestine nature of illegal migration. But the Global Commission on International Migration and Institute of Race Relations have long argued that illegal migration has become a structural and permanent feature of the country’s population dynamics. Some reports suggest the undocumented population could be between two and five million, although these figures remain speculative.

The socio-economic and political costs of irregular migration are often cited by critics of the government’s migration policies. Based on Professor Albert Venter‘s 2005 political risk model, as noted down by Machidi S Ngoasheng undocumented migrants can strain already overstretched public services and social welfare systems, particularly in health, housing, and education. The perception, and sometimes the reality of competition for scarce resources has fuelled xenophobic sentiment and periodic outbreaks of violence, which in turn strain South Africa’s diplomatic relations with neighbouring countries. For example, relations with Zimbabwe, Nigeria and Malawi have, at times, become tense following attacks on their nationals living in South Africa.

Civil society and political parties continue to play an influential role in shaping public discourse on immigration. While ActionSA and the Patriotic Alliance have pushed for stricter immigration enforcement and border controls, the Democratic Alliance has generally supported regulated immigration tied to economic opportunity and legal compliance.

The Economic Freedom Fighters, on the other hand, have condemned mass deportations and raised concerns about the financial and humanitarian costs of hardline immigration policies. The government spent more than R52 million deporting about 19 750 people during the period April to August 2024. The total number of deportations for the 2024-25 financial year reached nearly 47 000, an 18% increase from the previous year. Many of those deported re-enter, considering the risk worth incurring due to the desperate socio-economic conditions in the region.

Despite these problems, it is important to acknowledge the positive contributions that migrants make to South Africa’s economy and society. Many fill critical labour shortages, create businesses and bring cultural diversity. Effective migration management should not only focus on enforcement but also on integration, inclusion and sustainable development. A balanced and humane migration policy must consider the structural drivers of mobility across the region, such as poverty, inequality, and conflict, while also upholding the rule of law and national security.

While South Africa’s migration landscape is shaped by deep-rooted regional and global forces, it would be inaccurate to suggest that the country has consistently implemented evidence-based migration policies or applied them uniformly. Although frameworks such as the White Paper on International Migration (1999), the Refugees Act (1998), and the Immigration Act (2002) lay a strong legal foundation, their implementation has often been ad hoc, reactive and vulnerable to political influence. South Africa’s adoption of a non-encampment model for refugees and asylum seekers, rooted in a rights-based approach aligned with the Constitution and international obligations, is commendable in principle. It allows refugees to live freely rather than being confined to camps. But this model also presents significant administrative and logistical problems, particularly in ensuring access to services, legal protections and regular documentation.

One clear example of these difficulties is the persistent dysfunction within the asylum system, where application backlogs and lengthy appeals processes have left thousands in prolonged legal uncertainty. According to the United Nations Human Refugee Agency, South Africa continues to host one of the largest unresolved asylum caseloads globally, largely because of administrative inefficiencies and under-resourced institutions. These issues point to the urgent need for a more coherent, data-driven approach to migration governance that matches South Africa’s progressive legal commitments with practical capacity to implement them.

Another example is border management. Despite the creation of the BMA and increased investment in surveillance technologies, porous borders and corruption among officials undermine state efforts and contradict stated policy goals. To build a migration regime that is truly secure, fair and reflective of constitutional values, South Africa must commit to depoliticising migration governance, investing in institutional capacity and using reliable data to drive reform — rather than responding to public pressure or electoral cycles.

Leleti Maluleke is a peace and security researcher at Good Governance Africa.

31 May, 2025 | Admin | No Comments

The GAC GS3 Emzoom is a refreshing and a different offering in a flooded SUV market

It might come to the point where we lose track of how many Chinese brands there are in South Africa.

We might even begin to lose track of how many compact SUVs are in the market because it has become congested with them.

Chinese brand GAC Motor entered two SUV models into the South African market in the middle of 2024: the Emzoom and the Emkoo.

In typical fashion, both cars looked good and came with all the fancy technology that we have become accustomed to getting in Chinese cars.

The Mail & Guardian got behind the wheel of the Emzoom, which is available in three variants: Comfort, Executive and R-Style.

We were lucky enough to get the top-of-the-range R-Style model and I was pleasantly surprised.

I knew that the exterior and interior were going to be appealing, because Chinese manufacturers always put a lot of emphasis on bringing out a neat product.

However, I did find some styling similarities with BMWs. For starters, on the R-Line trim, the black grille gets three gold panels, much like some BMWs, which have M-specific colours on their grilles.

The colour coding on the inside also provided some similarities. The same blue plastics you see around the aircon vents in BMWs are present in the Emzoom R-Style.

This is probably because Thomas Schemera, who has held key roles at both BMW M and Hyundai, is now the chief operating officer and senior vice president of GAC International.

Alongside the ambient lighting inside the Emzoom, the air conditioning and volume dials also get a rainbow light around them. These style features give the car a fun and sporty atmosphere.

Manufacturers sometimes try too hard to make compact SUVs feel luxurious with fancy screens, decked out interiors and the absence of buttons. While the Emzoom still has the fancy screens and is decked out, it doesn’t aim for a luxurious interior, but rather something that boosts adrenaline.

The Emzoom comes with the standard 1.5 litre turbocharged petrol engine that we are accustomed to getting in Chinese compact SUVs. Paired with a dual-clutch transmission gearbox, it will deliver 130kW of power and 270Nm of torque.

The coolest feature of the car is the exhaust system which is designed to produce sound through “active exhaust valves”. These can be toggled between open and closed, allowing for a louder and more sporty sound when open, especially in the sport mode.

It adds to the fun feel the Emzoom was meant to have. You could actually fool people into thinking you were driving a sports car.

But this feature also has a downside. I became obsessed with the exhaust sound, continually putting the car into sport mode. This exposed the sensitivity of the accelerator, making the car move too quickly. This is not ideal when navigating into tight parking spots or even pulling into your garage.

Besides that, the Emzoom provides excellent handling and effortlessly picks up speed when you need it to.

I experienced some turbo-lag, but it was not bad at all. It didn’t make the vehicle feel unresponsive.

The other downside is the fuel consumption. This is a pretty compact vehicle and, while GAC claims a consumption figure of 6.2 litres/100km, I averaged 8.1 litres/100km.

Overall, I really enjoyed the GAC GS3 Emzoom. It felt different and refreshing. I loved the fact that GAC went all out in making it a fun and sporty experience without producing a performance monster.

You get everything you need — and the lovely exhaust sound as a bonus but, in a flooded SUV market, it is difficult to say whether the Emzoom will make a splash.

Pricing

GS3 EMZOOM 1.5L T Comfort — from: R419 900

GS3 EMZOOM 1.5L T Executive — from: R439 900

GS3 EMZOOM 1.5L T R-Style — from: R489 900

31 May, 2025 | Admin | No Comments

New law: Protecting South Africans from tobacco is no foreign agenda

The passage of the Tobacco Products and Electronic Delivery Systems Control Bill is a decisive moment for public health in South Africa. Yet, as we edge closer to enacting life-saving legislation, a familiar narrative has emerged, one that is designed to sow confusion and delay progress.

Accusations suggesting that the drafting of this legislation is influenced by foreign NGOs are not only baseless but strategically designed to detract from the real issue at hand: protecting our people, especially youth, from the harmful effects of tobacco.

South Africa ratified the World Health Organisation’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in 2005. The treaty obliges its signatories to adopt stringent public health measures and safeguard them from interference by the tobacco industry.

These obligations include consulting technical experts, researchers and civil society organisations to develop sound, evidence-based policies. This is not foreign meddling; it is the global standard for formulating robust tobacco control legislation.

The department of health led the drafting of the Tobacco Products and Electronic Delivery Systems Control Bill, working through established channels. Stakeholders across sectors as well as the broader public have weighed in, and parliament will review every aspect of the bill before its passage.

The narrative that South Africa is ceding its policymaking to external agendas is nothing more than an industry-led distraction. It is designed to confuse, politicise and derail a procedurally sound process that aligns with our constitutional and international commitments.

For decades, the tobacco industry has relied on diversion tactics, questioning the integrity of organisations and individuals who are advocating for public health reforms. South Africa is merely the latest chapter in this global playbook. But make no mistake, this bill is neither a foreign imposition nor the product of external pressure. It is the culmination of years of evidence-based recommendations and domestic public input, aligned with South Africa’s sovereign obligations under the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control.

The tobacco industry thrives not only on selling products that harm health but also on derailing policies that could save lives. Around the world, the industry has wielded its significant resources to manufacture doubt, discredit public health advocates and shift attention away from the substance of legislation — all to pave the way to profit from deadly tobacco and nicotine products, which include cigarettes, heated tobacco products and electronic cigarettes.

Whether in Pakistan, the Philippines or South Africa, the playbook remains the same: scatter unfounded accusations of foreign interference, ignite nationalist sentiments and bury meaningful discourse on protecting lives beneath conspiracy theories. The industry will use any tactic, including mischaracterising the policy process, to try to stop legislation that has an impact on its business.

South Africa is witnessing this tactic up close. Shifting the conversation away from the bill’s purpose, the industry claims that the government’s policymaking is compromised by external influence, even threatening litigation to challenge the legislation. Specifically, it is targeting the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids which, together with other experts, provided technical guidance during discussions on the bill. But this is what’s not being said. The campaign consultant involved is a South African citizen, a former director in the department of health, and someone with decades of experience in public health at both national and global levels. She is not a “foreign operative” but a lifelong servant to the health of this country.

The real purpose of the Tobacco Products and Electronic Delivery Systems Control Bill is to curb the harm caused by tobacco and nicotine products, particularly among the youth. Young people in South Africa are under siege; they’re targeted by an industry that relies on addiction to sustain its multibillion-dollar business model. Emerging nicotine products like e-cigarettes and heated tobacco are marketed with flavours, slick designs and celebrity endorsements that glamourise use while increasing dependence.

According to the Global Adult Tobacco Survey of 2021, 29.4% of adults in South Africa use tobacco products, smoked and non-smoked. A new national survey conducted for the African Centre for Tobacco Industry Monitoring and Policy Research, based at the University of Pretoria, shows that this had increased significantly, to 36.8% in 2024.

Tobacco smoking, specifically, has hit a high of 33.9% or 14.9 million, a prevalence level last seen in 1993. Use of novel tobacco products like e-cigarettes, heated tobacco products and oral nicotine pouches among young people aged 16 to 34 has risen to 13.5% or 2.6 million young people.

This burden translates to thousands of preventable deaths and a strained healthcare system. The new bill takes critical steps forward by proposing a comprehensive ban on smoking in public spaces, mandating standardised packaging, curbing advertising and prohibiting sales to children, as well as regulating unregulated novel products that didn’t exist when the legislation was passed.

Ironically, while lobbyists accuse public health advocates of being controlled by foreign entities, the tobacco industry itself is dominated by multinational corporations like British American Tobacco, Philip Morris International and Japan Tobacco. These profit-driven conglomerates, which operate in South Africa, are the real foreign entities that are prioritising shareholder returns over the health of the general population. Their financial interests lie in keeping South Africa addicted, not free from tobacco harm.

Time is critical when it comes to public health policymaking. Any delay in passing the bill equates to more lives being lost and more young South Africans becoming hooked on harmful products. By politicising public health discussions, the tobacco industry and its allies aim to manipulate timelines and erode momentum. Since the first publication of the bill in 2018 up to 2024, the total number of smokers has increased from 9.5 million to 14.9 million and vaping among young people has reached an all-time high.

At its core, this issue is simple — as South Africans, do we want to prioritise the profits of multinational tobacco companies or the health of our people? The delay tactics and conspiracy theories detract from the real questions we must ask our policymakers and ourselves as a nation. How do we safeguard future generations from the harm caused by tobacco? How do we align our policies with science and evidence? How do we ensure that multinational corporations cannot exploit our youth for profit?

The bill before parliament reflects a long-standing public health mandate, shaped by years of domestic input and aligned with our international obligations. Smoking-related illnesses claim about 40 000 South African lives annually. This bill offers a way forward and is a chance to break cycles of addiction, disease and suffering.

The time for decisive action has arrived. It is incumbent upon all of us to reject tactics that perpetuate harm and support measures that secure the well-being of our nation. The science is settled. The need is urgent. The delay is political. Choosing health is not only the right thing to do; it is the only thing to do.

Professor Lekan Ayo-Yusuf is the head of the School of Health Systems and Public Health at the University of Pretoria, director of the National Council Against Smoking and director of the Africa Centre for Tobacco Industry Monitoring and Policy Research.

Jazz has to be seen live to be appreciated. That might sound like a platitude that could apply to any genre of music but, for me, it was a revelation. As a person whose ears were more finely attuned to rap and rock from a lifetime of listening, every attempt I made to listen to jazz in the privacy of my home ended in failure. Until I experienced it live.

Some of the best moments of my life have been seated in a dimly lit room in front of a big jazz band. Nothing compares to seeing a six- or seven-piece ensemble playing at the peak of their powers, with an audience congregated to witness the holy communion of drums, bass guitar, double bass, piano, sax and trumpet.

It was only once I had worshipped at the church of a sold-out jazz gig, and sat in the presence of the genre being created live and in the moment, that I was able to appreciate it.

I had this on my mind last weekend when I encountered the booth hosted by Cape Town gallery Peffers Fine Art at the RMB Latitudes Art Fair.

What I found was an exploration of South African jazz seen through the discerning eyes of legendary photographers. It was an encounter with a hard-to-describe beauty, an attempt to capture the ephemeral magic that makes this genre of music so special.

The booth, a selection from the larger Back of the Moon exhibition, was the brainchild of Ruarc Peffers, often working with Matthew Blackman of the publisher Blackman Rossouw. Theirs is a fascinating, almost informal collaboration, where Blackman delves into the historical depths, unearthing narratives and forgotten faces, and Peffers brings a curatorial vision to the surface.

The idea for this compelling booth began somewhat organically.

“Initially, it started with Ruarc representing the Alf Kumalo estate and then also working with the Baha Archives,” Blackman recounted.

A casual conversation about the Journey to Jazz Festival in Prince Albert led to the idea of an exhibition.

“I made an offhand comment that maybe we could do an exhibition of jazz photography with them,” Blackman shared.

This initial focus on Kumalo’s work gradually expanded: “As the project developed, we began to pull in all of the other photographers of that era. And then, you know, we finally pulled in the Ernest Cole photographs from the final chapter of the republished House of Bondage book.”

The Latitudes showing felt like a concentrated essence of that larger exploration, a collection of moments plucked from a rich and resonant past. The exhibition ultimately featured the work of not only Kumalo and Cole, but also Bob Gosani, GR Naidoo and Jürgen Schadeberg.

Walking through the booth, I was struck by the way these photographers, each with their distinct approach, managed to capture something beyond the mere visual representation of musicians.

There were the familiar giants, Hugh Masekela and Miriam Makeba, their images carrying the weight of their immense cultural impact.

But it was the glimpses of lesser-known figures that truly resonated.

Blackman’s research illuminated the story of Gideon Nxumalo, a jazz innovator whose contribution in the Sixties deserves far more recognition.

He found it interesting “how there are these forgotten figures in our jazz history and … how truly incredible they really were among them”.

To see Nxumalo captured at his piano by both Kumalo and Cole felt like witnessing a vital piece of history reclaiming its rightful place.

Similarly, the photographs of Philip Tabane and Julian Bahula, pioneers of the Malombo Jazz Men, spoke to a crucial shift in the South African jazz landscape, a move towards a more homegrown sound. Through the lenses of Cole and Kumalo, their revolutionary spirit was palpable.

This wasn’t just a random assortment of photos. It felt like a deliberate curation of narratives. Some images were instantly recognisable, having become ingrained in our collective memory through album covers and publications.

“There’s the famous Miriam Makeba by Jürgen Schadeberg, which was an obvious one,” Blackman noted.

But it was the discovery of previously unseen or misidentified photos, particularly from the Ernest Cole archive, that held a particular allure.

Blackman recounted the detective-like process of identifying subjects.

He found it “interesting that there’s so many photographs in our archives that are sort of unidentified”.

These rediscoveries underscored the depth and untapped potential in our photographic archives.

Even a seemingly simple image of Masekela with a trumpet-maker, unearthed and correctly identified, held a quiet power, a glimpse into the everyday life of a legend.

“That was actually the one, interestingly, that Hugh’s daughter had never seen before,” Blackman shared, highlighting the fresh perspective these discoveries brought.

What, then, makes a jazz photograph truly special? It’s a question I pondered as I moved from frame to frame. Jazz, at its core, is an improvisational, atmospheric art form.

How do you capture the fleeting beauty of a saxophone solo, the rhythmic pulse of the drums, in a static image? Blackman articulated this challenge beautifully: “Jazz, being music, is obviously an art form, which is one that is difficult to represent in written language … But a photo can capture the kind of poetry of that music because there’s movement and obviously atmosphere.”

The most compelling jazz photographs are those that transcend mere documentation. They aren’t just about who was playing but about the feeling, the communication between the musicians, the sheer immersion in the act of creation.

Alf Kumalo’s image of Winston Mankunku, shrouded in cigarette smoke, his saxophone a conduit for something profound is an embodiment of a mood, an era, a feeling.

Blackman pointed out some were posed due to the limitations of the equipment. “Many of the early photographs are of jazz musicians posing as if they are in a jazz club rather than actually being in the jazz club.”

Yet, even in these staged moments, there’s an attempt to convey the spirit of the music. As technology evolved, photographers gained the ability to capture the raw energy of live performances.

But, regardless of the setting, the great photographs capture moments of intense focus, where the musician is utterly lost in their craft. They’re often not looking at the camera; they’re in conversation with their instruments, with the music.

There’s something inspiring, almost primal, about witnessing that level of dedication frozen in time.

“The key is it’s a photographer, who is an artist capturing somebody … making art themselves; there’s this beautiful symbiotic connection.”

The response to the booth was enthusiastic and culminated in it winning the audience choice award.

“I was really delighted to see how many young people were coming through, recognising who some of these jazz musicians were and taking selfies next to them,” Blackman said.

Leaving the booth felt strangely akin to leaving a jazz gig, my senses still ringing with the rhythm of what I’d just experienced, reluctant to return to the silence outside.

Just as it took witnessing jazz live for me to truly understand its power, it took standing face to face with these photographs to realise how deeply the genre’s energy lives beyond the music itself.

There, suspended in stillness, was the very essence I had first encountered in a crowded, low-lit room — the pulse, the presence, the communion.

These images didn’t just show me jazz. They made me feel it, again.

31 May, 2025 | Admin | No Comments

A movement against silencing: What the war in Palestine has taught us about journalism

One of the most revealing takeaways from the genocide in Gaza has been the profound threat posed to journalism. Even in this era of artificial intelligence and disinformation, truth remains a powerful force. And the most brutal way to silence truth is to eliminate those who report it.

This has been the clear strategy adopted by Israel. A recent study found that more journalists have been killed since 7 October 2023 than in any other conflict in modern history — more than the total deaths combined in the U.S Civil War, World War I, World War II, The Korean War, Vietnam, Yugoslavia, and post 9/11 Afghanistan.

A Lancet report estimated that Palestinian deaths are 40% higher than figures provided by the Palestinian Ministry of Health. At the time of writing, the official toll stood at 54,056 but the actual number may be closer to 100,000. Similarly, the number of journalists killed continues to climb, reported at 232 deaths in April 2025 but has grown after several more targeted attacks since, hence we can estimate that death toll to be 250 by May 2025. In all likelihood, the actual figure is far higher.

On the Ground in South Africa

In 2022, I was approached by the Salt River Heritage Society in Cape Town to speak about the murals they had commissioned in their neighbourhood. Central among them was one depicting Shireen Abu Akleh, the Al Jazeera journalist assassinated by an Israeli sniper on 11 May 2022. Initially, Israeli authorities falsely blamed Palestinian militants. By the time her murder was verified, the media cycle had moved on. A full year later, on 12 May 2023, the Israeli Defence Force issued a hollow apology. Shireen’s killing epitomised a strategy of “killing the truth” — the deliberate targeting of journalists, a war crime under international humanitarian law.

Cape Town, more than any city in Southern Africa, has consistently demonstrated loud and visible support for Palestine. Since the genocide began, countless events — marches, murals, boycotts, motorcades, talks, exhibitions, concerts, interfaith gatherings, and vigils — have been held.

Just two weeks into the onslaught, on 22 October 2023, I was invited by the Palestinian Solidarity Committee (PSC) to speak at the first major protest for Gaza, again in Salt River, specifically to address the killing of journalists. At that point, 17 journalists had already been murdered. No one could have predicted the escalation that followed.

Since then, my commitment to this issue has only deepened. As an independent journalist and freelancer, I have had the privilege of speaking freely — at protests, on radio, television, and social media — during a time when many employed journalists feared for their jobs. I’ve used my voice with the hope that it might echo enough to spark accountability. So far, that hope remains unfulfilled.

Yet despite over 600 days of relentless bombardment and destruction, young journalists in Gaza persist. One of the most remarkable examples is nine-year-old Lama Jamous, who donned a press vest and began reporting from the ruins of her neighbourhood.

Perhaps the most meaningful solidarity effort in South Africa was the organisation of national vigils on 28 January 2024. Held in Cape Town, Johannesburg, KwaZulu-Natal, and Makhanda, these gatherings condemned the systematic murder of Palestinian journalists. Journalists across the country united to honour their colleagues abroad. In Cape Town, award-winning journalist Zubeida Jaffer spoke movingly about her experiences reporting during apartheid and covering the Rwandan genocide — drawing clear parallels with Gaza. Many veteran journalists agreed: the conditions Palestinians face today are even more brutal than those under South African apartheid.

From these vigils emerged a WhatsApp group called Journalists Against Apartheid, a platform for solidarity, awareness, and resistance among South African media workers.

A Divided Media

The genocide in Gaza has unmasked the stark divide in global journalism. Palestinian journalists have redefined what it means to do this work. Their commitment isn’t driven by money or recognition — it is a moral imperative. Despite losing homes, loved ones, and access to basic needs, they continue reporting. They’ve carried injured children into hospitals, buried colleagues, and dug survivors from rubble — all while documenting the unfolding horror. They appear on our screens, exhausted yet unwavering, embodying what it means to serve truth.

In contrast, Western media has disgraced itself. It has become a factory of bias, Islamophobia, and propaganda. One of the most damaging cases emerged on 14 October 2023 — the viral lie that Hamas had beheaded 40 babies. First shared by Israeli soldiers, the claim was repeated by then-U.S. President Joe Biden without evidence. The result? A white supremacist in Chicago murdered six-year-old Palestinian-American Wadea Alfayoumi in a hate crime — stabbing him 26 times. Only in May 2025 was the perpetrator charged. To date, Israel has not retracted or apologised for the lie that sparked the killing.

Western journalists have become cheerleaders of empire. Major networks like BBC and MSNBC fired journalists for supporting Palestine. Outlets like CNN and The New York Times led with fake headlines and unverified stories — many of which were later retracted, but not before irreparable harm was done.

Palestinian writer Mohamed El Kurd described this propaganda machine best:

“A claim is circulated without evidence; Western journalists spread it like wildfire; diplomats and politicians parrot it; a narrative is built; the general public believes it — and the damage is done.”

In response, citizen journalism has risen powerfully. Platforms like Instagram and TikTok have become vehicles for truth, elevating voices on the ground. Ordinary people, wearing “PRESS” vests, risk their lives to document reality. The use of mobile phones makes Israeli atrocities harder to conceal — though the regime has responded with censorship, shadowbanning, and algorithmic suppression.

A Commitment to Truth

In October 2024, Al Jazeera correspondent Youmna El Sayed visited South Africa. Hearing her firsthand account was life-changing. Younger than me, yet infinitely more brave, she described war from the perspective of a mother and journalist. Speaking in Cape Town’s Bo-Kaap, she recounted being given five minutes by Israeli forces to evacuate her home with her husband and four children.

“My 8-year-old daughter Sireen’s biggest fear was surviving alone,” she said.

“Every night she asked us to sleep close together and said, ‘Mom, if a rocket hits, let it kill us all so no one is left behind.’”

El Sayed spoke of displacement, the stench of decaying bodies, and the total dehumanisation they endured.

“Journalists in Gaza were targeted everywhere: in our homes, in the field, in our cars — with no mercy and no regard for humanitarian laws.”

“Israel barred international journalists from entering Gaza, hoping to hide its crimes. But it underestimated the resilience of Palestinian journalists — continuing to work with no food, no water, and bombed-out offices.”

We all remember the moment veteran journalist Wael Al-Dahdouh cradled the lifeless body of his son Hamza — also a journalist — killed while Wael was reporting. We remember 23-year-old Hossam Shabat, who wrote a letter before his death in April:

“Now I ask you, don’t stop talking about Gaza. Don’t let the world turn its eyes away. Keep fighting, keep telling our stories — until Palestine is free.”

The death toll among journalists will rise, as the genocide continues. But rather than deterring us, these deaths strengthen our resolve. We remain committed to ethical journalism, to truth-telling, and to bearing witness to injustice.

We will not be silenced. We owe that to those who gave their lives so the world could see.

*This article was first published in Media Review Network on 28 May 2025

Atiyyah Khan is a journalist, activist, cultural worker and archivist. For the past 17 years, she has documented the arts in South Africa. Common themes in her work focus on topics such as spatial injustice, untold stories of apartheid, jazz history and underground art movements.

Melville, once declared one of the world’s hippest neighbourhoods, is in serious decline. The suburb is an important asset to our academic life and must be restored.

I often host students and faculty from universities in Europe and the US. For a long time, Melville was the automatic place for academic visitors, professors and students to visit and stay while passing through Johannesburg.

Located next to the University of the Witwatersrand, one of our two great universities, as well as the up-and-coming University of Johannesburg (UJ), Melville has long provided a convivial environment for academics and post-graduate visitors. In 2020, just five years ago, Time Out magazine ranked Melville as one of the 40 coolest neighbourhoods in the world.

Academic travel matters, and academics want to enjoy their experience of travel. For decades Melville, buzzing with coffee shops, restaurants, live music venues, galleries and a very good second-hand bookshop provided exactly what academics and post-graduate students needed to enjoy their time in Johannesburg.

The turn to Zoom during Covid has reduced academic travel quite a bit, but spending two days on Zoom rather than travelling for a conference is a painful and vastly less rewarding experience.

Melville was hit hard by the Covid lockdown though, and has been hit just as hard by the general collapse in the functioning of the Johannesburg municipality.

Many of the restaurants on the once world-famous 7th Street shut down during the lockdown and many of the buildings on the strip remain empty. If there had been some vision to support the strip, understanding it as a wider asset to the city, and the country, this could have been avoided.

Driving into Melville recently with a group of students and academics was a depressing experience. Coming up Main Road, which divides Melville and Westdene, is bleak.

There are three large holes, which are so big they cannot be described as potholes, on Main Road that have been left unattended for months — aside from placing a plastic barrier in front of them.

Some of the shopkeepers dump their refuse on the pavement next to the pedestrian litter bins rather than keeping it for the weekly refuse collection.

The homeless people on Main Road, many struggling with addiction, live in squalor and the lack of public toilets has inevitable consequences.

Uber and delivery drivers face the same lack of access to toilets with the same unfortunate results.

Turning into Melville itself is no less disheartening. Streets no longer have working lights, there are a couple of abandoned and looted or vandalised houses, and some of the electricity poles have a mess of dangling wires, some live.

Around the suburb piles of rubble have been left on the pavements after work done by Egoli Gas and various arms of the municipality. It seems that it is no longer expected that rubble will be removed after maintenance work alongside the streets.

The 7th Street strip, with its many empty buildings, has large ditches filled with sand at each end. They have also been there for months.

On the corner of 3rd Avenue and 7th Street, part of the road has been left in a dug-up state and with a pile of rubble sitting on the road. It too has been like this for months.

Private property owners are beginning to do the same. On the corner of 2nd Avenue and 7th Street a homeowner has left two large piles of building rubble on the pavement for months.

A slow water leak has been trickling down 7th Street for months. There are no drain covers on the strip. This is unsightly and a hazard for pedestrians. The road markings have long faded away. Anyone on the strip who looks like they may have some money is immediately accosted by desperate people trying to get a few rand.

Water outages are common in the area, sometimes going on for as long as two weeks. There are also occasional electricity outages that can go on for days. This makes things very difficult for the owners of the B&Bs that remain in the neighbourhood, as well as the surviving restaurants and other businesses.

Driving out of Melville on 9th Street towards Parkview, a suburb that remains in good nick, there are more piles of rubble on the pavements and more deep holes in the road. As on Main Road, both the rubble and the holes have been left for months.

It is not immediately clear why nearby suburbs such as Parkview, Greenside and Parkhurst are in a good condition while Melville is in decay.

An academic neighbourhood requires a good bookshop and, thankfully, the good second-hand bookshop on the Melville strip endures, but it’s no longer open in the evenings. There are some signs of new life after the devastation of the lockdown though. De Baba, a new bakery and coffee shop at the bottom of the strip is always buzzing.

On the other side of the road there’s a new and very hip coffee shop, Sourcery. It would fit right into Brooklyn, New York, and is perfect for an arty and academic neighbourhood like Melville. A vinyl-obsessed friend tells me that the music selection is extraordinary. Unfortunately, Sourcery seems empty most of the time. The same is true of Arturo, an excellent and equally hip African Latin-American fusion restaurant further on up the strip.

Some of the problems faced by Melville are a result of South Africa’s wider social crisis. For as long as we face catastrophic levels of unemployment people will be forced to live on the streets. The heroin epidemic is also a national problem. Although the municipality can take some steps to ameliorate some of the consequences of these problems it cannot fix them.

But much of the sad state of Melville is a result of the failures of the municipality. Some of these failures could be resolved in a single day. Light bulbs could be installed on the street lights, the large holes on Main Street, 7th Street and 9th Street could be fixed, the rubble left along the pavements could be removed, the water leak on 7th Street could be attended to and the road markings redone.

The private businesses dumping their waste alongside the pedestrian bins on Main Road could be fined, as could the private homeowner who has left piles of building rubble on the corner of 2nd Avenue.

Other issues that fall within the remit of the municipality, such as the failure to provide public toilets on Main Road, cannot be resolved in a day, but with some vision and energy they could be resolved in a few months.

Getting the water and electricity systems functional is a much bigger project but is also something that can be achieved with the right commitment. The abandoned properties, with at least one house stripped to nothing but its walls, should be expropriated and sold, with the money invested into regeneration projects.

There should also be active support, including subsidies, for art galleries and live music venues. All the world’s great cities actively support cultural life and the same should be done in Johannesburg. Again, this is something that would, even with the right vision and commitment, take at least a few months to kick into gear.

When Melville was the vibrant and world-regarded home to Johannesburg’s arty and academic scene it was a major asset to the city. It was an asset to the city’s residents, and to visitors to the city, including its wider tourism economy. Melville was also an important asset to the city’s two universities, making visits by academics and post-graduate students from elsewhere in the country and abroad an enriching and fun experience.

There is scant hope that the municipality will, on its own, take the initiative to act to restore Melville to what it once was and can easily be again.

Universities are powerful institutions in society; Wits University and UJ should lobby the municipality to act to restore Melville as one of the world’s great academic neighbourhoods. A well maintained and vibrant Melville would be a boon for the city.

With the right commitment it would only take a single day to begin to turn things around.

Dr Imraan Buccus is a research fellow at the University of the Free State and the Auwal Socioeconomic Research Institute, ASRI.

31 May, 2025 | Admin | No Comments

South African firms suspect UAE companies may have obtained military intellectual property

Defence company Paramount Group has provided information to the Special Investigating Unit (SIU), which is investigating claims that companies in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) unlawfully obtained intellectual property developed by South Africa’s arms industry.

The investigation focuses on employees of at least two defence firms who are suspected of passing military intellectual property (IP) to UAE state-owned companies.

“Paramount Group is cooperating fully with the Special Investigations Unit (SIU) in its investigation into wrongdoing by UAE government-controlled entities, particularly as it relates to the unlawful targeting of South African defence intellectual property,” Lynn Lauth, a lawyer for Paramount, told the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), a global network of investigative journalists.

The OCCRP obtained two briefings from the SIU, which focus mainly on allegations that employees of a second company, Denel SOC Ltd, “misappropriated” the research and design that underlines arms production.

One of the documents obtained by the OCCRP was a 2023 presentation to parliament’s standing committee on public accounts (Scopa), while the other was a PowerPoint briefing of the SIU’s findings in 2025.

The SIU declined to answer detailed questions about its investigation, saying that it “reports only to the president and parliament”.

“Therefore, we cannot make public statements or give comments on ongoing investigations,” a spokesperson added in an email. “However, it is important to note that evidence indicating criminal conduct has been referred to the National Prosecuting Authority.”

Paramount has also launched its own internal investigation to determine whether employees provided intellectual property to a UAE company after a joint venture deal that eventually collapsed.

‘Pattern of misconduct’

Founded in South Africa in the early 1990s, Paramount is now headquartered in the UAE. The company filed for bankruptcy last year after losing an arbitration case in London against Abu Dhabi Autonomous Systems Investments Company (Adasi).

Paramount’s problems began in 2016 when one of its subsidiaries, Riverston Enterprises Limited, entered into a joint venture deal with Adasi.

The joint venture fell apart after Adasi was taken over by another UAE state-owned firm called Edge Group, according to internal records and court documents obtained by the OCCRP.

As part of the agreement to set up the joint venture, Adasi had provided Paramount with a loan of $150 million, an internal document from Edge shows. That money was meant to cover the costs of creating the joint venture company in the UAE, and transferring the intellectual property behind Paramount’s reconnaissance plane, which the new company would transform into an armed strike aircraft called the MWARI.

Both Adasi and Paramount agree that the intellectual property was never transferred to the UAE as planned. Now Paramount says it is no longer legally obligated to transfer the intellectual property, but Adasi says it has the rights to the information under the arbitration ruling.

Neither the Edge Group, which owns Adasi, nor its public relations representatives responded to requests for comment. But a legal document filed by Adasi in Paramount’s bankruptcy case provides insight into its position.

In the legal filing, Adasi argued that Paramount’s bankruptcy case was a stall tactic meant to give the company time to move its assets so they could not be transferred. Those included the “potentially valuable intellectual property assets”, which had been “granted to Adasi”.

The filing states that Paramount said it declared bankruptcy because it could not afford to pay the penalty ordered by the arbitration board. That penalty totalled $230 million, and included the $150 million that was to cover the transfer of intellectual property for its aircraft to the UAE.

Paramount’s South African lawyer, Lauth, told the OCCRP that the intellectual property of the MWARI aircraft “remains wholly governed by South African law and has not been externalised to the UAE, Adasi, EDGE or any related entity”.

Intellectual property used exclusively for military purposes is often not patented, because doing so would make the designs accessible to competitors and hostile actors. Instead, such property is considered a “sovereign asset” overseen by the government, according to experts including Vanessa du Toit who previously ran the National Conventional Arms Control Committee, which oversees South Africa’s military technology and arms exports.

Lauth said the research and design behind the MWARI was “not the only intellectual property that was allegedly targeted”.

“Our clients have identified a broader pattern of misconduct involving multiple Paramount-developed platforms,” she told the OCCRP.

In a leaked document from the arbitration case, Paramount founder Ivor Ichikowitz said the deal was based on Adasi ordering 5 000 armoured vehicles, and 6 000 “loitering munitions”, which are drones built to explode on impact. In the end, only four trucks and 500 drones were ordered by the company.

“In hindsight, it now appears that the presentations and solutions we presented may have been used by … staff to benchmark other defence projects underway at the time in other organisations in the UAE,” Ichikowitz said, according to a leaked affidavit from the arbitration case.

Ichikowitz declined to provide comment to reporters.

Martie Baumgardt, a senior executive, told the OCCRP the firm is also carrying out its own internal investigation. She said the company is looking into the “possible theft of IP from Paramount by individuals who left the company, which may conceivably have ended up in the UAE”.

According to Baumgardt, after the joint venture with the UAE partner broke down, 45 Paramount employees joined Edge Group companies.

A leaked document from Paramount’s internal investigation also alleges that 57 laptops and 10 hard drives were stolen from 2016 — the year Paramount’s subsidiary entered the joint venture with Adasi — to 2024, when it lost the arbitration case.

The Denel affair

Meanwhile, the Denel case dates back to 2012, when South Africa’s state-owned arms manufacturer entered into a joint venture with a UAE firm, then known as Tawazun Operation Company LLC. Under the agreement, the two firms established a new company based in the UAE called Tawazun Dynamics LLC.

According to the 2023 briefing to Scopa, the joint venture was initially intended to manufacture and supply Denel missiles to the UAE Air Force, and “future customers”.

At first, the partnership appeared to be a success. Other deals were soon struck, in which Denel would also provide a UAE defence company called NIMR Automotive LLC with RG35 Military Vehicle IP and hardware.

But the relationship began to sour.

“It is alleged that the IP belonging to the institution was misappropriated in cohesive criminal conduct to abet foreign state companies,” the SIU said in its 2023 briefing, referring to allegations brought by Denel.

In its investigation, the SIU found evidence suggesting that Denel employees may have accessed intellectual property without permission.

In one instance, SIU investigators found that “data packs” relating to missile technology had been downloaded from Denel’s system after a request from Halcon, another arms company owned by Edge Group, according to the 2023 briefing.

That briefing also outlines a case reported by Denel to the SIU, which involved intellectual property for a military vehicle. The SIU noted that contracts had been signed with NIMR by a Denel employee who was not authorised to do so.

“This official later resigned and informed Denel that he was offered a senior position by NIMR,” the briefing says.

Denel reported that it had later received a letter from the chief executive of NIMR, who had previously worked for Denel, demanding intellectual property for a military vehicle.

The joint venture company Tawazun Dynamics is today called Al Tariq and — like NIMR — it is owned by Edge Group, which did not respond to questions about alleged attempts to transfer intellectual property from Denel.

The NIMR chief executive was one of more than 300 Denel staff who left the company and went to work in the UAE’s arms sector, according to a summary of a South African parliamentary discussion in February.

Gloria Serobe, chair of the Denel board, told the parliamentary committee that so many Denel employees had left for UAE firms that “board meetings were done in Afrikaans”.

This story was first published by the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP).

30 May, 2025 | Admin | No Comments

Conventional and complementary healthcare professionals need to work together

Earlier this year, the US government took the drastic decision to terminate about 40 USAid-funded health projects in South Africa, a move that threatens the sustainability of these projects. The halting of funding has led to the closure of many clinics and a decrease in services rendered, such as HIV testing and treatment.

To mitigate the problem, the health department, together with the South African National Aids Council, the Joint UN programme on HIV/Aids and World Health Organisation, has launched the Close the Gap campaign, which aims to put 1.1 million individuals living with HIV on treatment by December 2025.

But this intervention leaves a gap of more than 2 million people who are lost to treatment for different reasons. According to the health department, nearly 8 million people are living with HIV in South Africa, with 5.7 million people stable on antiretroviral drugs (ARVs).

Among the reasons for the lost numbers could be the use of complementary medicine, instead of the conventional medicine offered in the mainstream healthcare system. Despite South Africa having diverse communities with multifaceted healthcare needs, who seek assistance from both conventional and complementary medicine practitioners, research shows that access to complementary medicine remains largely unsupported. According to the WHO, 80% of the world’s population uses it.

Complementary medicine includes treatments such as homeopathy, Unani-Tibb, ayurveda, traditional Chinese medicine, aromatherapy and Western herbal medicine. South African studies have highlighted the high use of complementary medicine, especially Western and traditional herbal medicine, among people living with HIV.

Additionally, these studies have shown that people living with HIV use complementary and ARVs concurrently without the knowledge of their healthcare providers. This is a huge risk as it can compromise the safety and effectiveness of ARVs and cause herb-drug interactions. This is exacerbated by the lack of inter-professional communication between conventional and complementary healthcare practitioners.

Professional inter-referral is a practice of healthcare practitioners referring patients to other practitioners to ensure complete, safe and high-quality patient-centred care. This practice is a requisite to improve patient outcomes and enhance the efficiency of healthcare delivery.

Despite the increasing evidence and popularity of complementary medicine use in South Africa, there is no formal inter-referral system between conventional and complementary healthcare professionals. Studies show that conventional healthcare practitioners do not refer patients to complementary practitioners, even though they receive referrals from them. For instance, complementary medicine practitioners refer patients to hospitals for laboratory blood tests and X-rays, as well as to various specialists.

This finding is concerning and needs to be highlighted to improve the management of multidisciplinary care and continuity of patient care.

Furthermore, evidence shows that the lack of an inter-referral system between conventional and complementary practitioners can lead to the fragmentation and compromise of the delivery of quality healthcare. This suggests that inter-referral relationship is a significant practice needed for comprehensive patient care, especially in South Africa, where diverse people use different modalities for healthcare.

It demands that healthcare practitioners realise that their area of expertise is important — but not sufficient alone. This is not easy for some to accept and warrants highlighting. Inter-referral relationships require practitioners to step outside their professional pride to appreciate others.

A 2025 South African study showed that conventional healthcare practitioners were willing to suggest that patients seek advice from complementary practitioners, yet they were unable to make a formal referral themselves.

One can assume that conventional practitioners might have a perception that practising complementary medicine is not a legitimate profession. Their insufficient knowledge of complementary medicine could also be a reason for not referring patients.

In South Africa, complementary medicine is regulated by the Allied Health Professions Council of South Africa. The licensing and registration requirements are regulated by the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority. These bodies prioritise the quality and efficacy of medicines and patient safety.

Complementary healthcare practitioners are clinically trained as diagnosticians in higher institutions across South Africa. For instance, the Department of Complementary Medicine at the University of Johannesburg offers a postgraduate diploma in phytotherapy (medicinal plant-based therapy) to medical doctors to increase their scope of practice, enhance the cross-disciplinary approach and help them provide a holistic treatment for patients.

The dominance of evidence-based medicine is identified as the main barrier to the inter-referral system. There is increasing documented scientific and clinical evidence on complementary medicines and safety data on the toxicology and possible herb-drug interactions.

This evidence is sufficient to convince conventional healthcare practitioners to refer patients to complementary practitioners. A formalised referral system is significant to strengthening the healthcare system, especially within the integrated National Health Insurance that is to be implemented in South Africa. The lack of a formalised inter-referral system has implications for patient safety in the delivery of healthcare.

The delivery of healthcare in South Africa needs to be considered alongside the broader cultural and social contexts, which necessitate a collaborative approach. South African healthcare must offer a holistic patient-centered approach that considers patients’ preferences and includes them in the treatment plan. This will ensure that patients receive appropriate service according to their needs.

Dr Tebogo Tsele-Tebakang is head of the Department of Complementary Medicine, in the Faculty of Health Sciences, at the University of Johannesburg. She writes in her personal capacity.

There it was in stark black and white, the sad news that legendary Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado had died at the age of 81 in Paris. It is terrible news but the great man lived a full life travelling to the remotest corners of the world to document the lives of people, the environment and the relationship between the two.

Sometimes brutal but always beautiful, his images of human suffering led some to call him the “aesthete of misery”. Probably his most well-known image is the one of hundreds of workers at the Serra Pelada gold mine in Brazil swarming up crude wooden ladders weighed down by heavy containers.

But there are thousands of other equally unforgettable images — always black and white and often with the contrasts of light accentuated — from Salgado’s trips to the wildest areas on Earth, from the Amazon to the Arctic.

In the documentary The Salt of the Earth, co-produced by German director Wim Wenders and Salgado’s son Juliano Ribeiro Salgado, the acclaimed photographer, a man after my own heart, says: “We humans are terrible animals.”

Something that I didn’t know about Salgado is that after experiencing the horrors of the Rwandan genocide, in 1998 he put aside his cameras and founded the Instituto Terra. In a grand reforesting project he planted hundreds of thousands of trees in the Rio Doce valley in Brazil.

Amid the relentless barrage of stories about the forests being chopped down, or cleared to make room for planting, or just burnt in raging fires caused by climate change, these projects offer a glimmer of hope. And the sheer numbers of the trees planted are truly awe-inspiring.

India has an impressive number of inspiring characters who are leading the way in reforestation projects. Jaggi Vasudev, more commonly referred to as Sadhguru, founder of the Isha Foundation, says his ambition is to plant 2.4 billion trees. And with his gleaming white turban and flowing white beard the yogi, mystic, teacher and author has the gravitas to convince even the doubters that this ambitious plan is completely achievable.

Here in Johannesburg we are constantly told we live in “the biggest man-made forest in the world” with more than 10 million trees growing in the city.

But Johannesburg is in danger of losing its place as the leading tree destination in the world, because our trees are not immune to the city’s dangerously high crime rate. As yet the trees don’t have a category in the crime stats, but if the rate of attrition continues to climb, the police commissioner will be reeling off some depressing figures of deaths, damage and murders.

The biggest culprit is the aptly named shot hole borer, also known as PSHB (the P stands for polyphagous, which means the beetle can feed on multiple types of trees).

Here is an expert definition of this criminal’s modus operandi: “The beetle infests trees by tunnelling deep into the trunk or branches and depositing a fungus that effectively poisons — and eventually kills — the tree. If the tree is a PSHB ‘reproductive host’ species, then the borer will reproduce in the tree at an alarming rate: a reproductive host tree can house up to 100 000 borer beetles. The offspring then fly out of the host tree and infest more trees.”

Evidence of this habitual criminal’s killing spree can be seen all over Johannesburg. Bare, blackened tree skeletons with rotting branches.

Unfortunately the lethal little bug is not the only criminal attacking our trees. Humans won’t let a two-millimetre sized insect from Vietnam outdo them when it comes to murdering trees.

I have seen jacaranda trees viciously attacked by chainsaw-wielding suburbanites because they are unhappy with the “mess” from the leaves and the beautiful mauve blossoms when they fall.

I have seen a majestic plane tree in Bez Valley ruthlessly sawn down at ground level because a homeowner had opened a hair salon in his garage and didn’t want the tree to impede the entrance.

I have seen massive oak trees subjected to hideously slow deaths by criminals who set fire to piles of the trees’ own leaves at the base of the trunk.

These are trees that are on the pavement and supposedly belong to the city, but much like the smash-and-grabbers at traffic lights or armed hijackers who drive off with your car, not many of the tree killers are brought to justice.

The problem here might be that all of the trees mentioned are what is politely termed “exotics” brought in from Europe and South America to line the streets of the first suburbs of the rapidly expanding city. Some, like the jacaranda, adapted so well to their new home and reproduced so abundantly that they have been declared “alien invasive plants guzzling up all the town’s water and are harmful to the environment and surrounding species”.

Sounds familiar doesn’t it?

Even by today’s standards the tree situation cannot be called a genocide but Sebastião Salgado would surely have found inspiration here for his searing photographs.

30 May, 2025 | Admin | No Comments

City of Cape Town investigates International Peace College building project

The International Peace College South Africa (IPSA) has been accused of illegally occupying part of a refurbished building in Cape Town after failing to submit building plans and appoint an engineer to oversee construction of the revamp project.

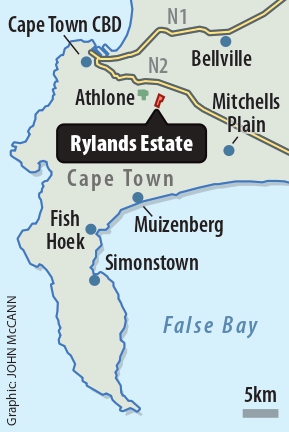

Whistleblower Salma Moosa, an interior architect who previously worked on the project in Rylands, told the Mail & Guardian about her year-long battle to get the City of Cape Town authorities to confront the matter.

The IPSA has vehemently denied the allegations as “unsubstantiated, defamatory, and malicious”. The City of Cape Town has confirmed that construction work went ahead on the project without complying with building regulations.

Moosa said she had sent emails to the city, including to mayor Geordin Hill-Lewis, the office of the city ombudsman and the fire department in November 2024 but had not received a response to her complaint about the failure to submit building plans for months, apart from being told that the city’s legal department was awaiting a court date.

In the meantime, she noticed that the building had been occupied.

In her letter to Hill-Lewis, Moosa alleged that construction had continued on the site despite the city having issued a stop work notice to the IPSA on 18 April 2024.

“Despite my insistence that a structural engineer be appointed, the client refused to do so. I even went as far as bringing a structural engineer to site to evaluate the work … [The] municipality will be held accountable if the structure fails and there is a loss of life, as I have raised these concerns with the relative building inspectors for the area via telephone,” Moosa wrote.

“I am concerned about the safety of the students as it is a public building, and it is currently being used.”

Moosa alleged building works proceeded with no professional engineer being appointed, no structural design plans, no sign-off of construction work and no architectural building plans were submitted or approved for the building works.

“The subcontractor did not follow any of the construction regulations for establishment of the site,” she alleged. “The building is currently being utilised for teaching despite no occupational certificate issued.”

Moosa said she eventually received a letter from the city’s ombudsman on 15 May advising that the office was in the process of “registering and assessing the matter” but this was only after the M&G had prodded the city regarding her complaint.

She said she felt it was her moral duty to blow the whistle on the non-compliance with the building regulations.

Cape Town’s deputy mayor and mayoral committee member for spatial planning and environment, Eddie Andrews, confirmed Moosa’s fears in his response to the M&G’s questions regarding the status quo of the development.

“The work done contravenes section 4(1) read with section 4(4) of the National Building Regulations and Building Standards Act No 103 of 1977. The owners started with building on site prior to obtaining written approval from the local authority for such work,” Andrews said.

“No building plan applications have been submitted to date, hence the matter is referred to the city’s legal services department.”

He added that it followed that “no occupancy certificate has been issued, as no building plan has been approved”.

Asked why the city had not forced the developer and the IPSA to comply with its stop work notice, Andrews said it was taking legal steps to enforce compliance.

“Due to non-compliance with the notices served on the registered owners, the matter was referred to the city’s legal services department for prosecution/further processing to the municipal court,” he said.

“We are awaiting feedback from the processing office at legal services to determine where in the process the matter is. At this stage the matter is still being investigated by the city’s legal services department.”

Moosa said she had dealt with IPSA representative Nazier Osman regarding the project’s construction work and interior design.

Osman referred the M&G’s request for comment to the college’s attorney, Edwin Petersen, who, acting for Osman and the IPSA,demanded that the M&G retract the story and threatened legal action.

Petersen said the allegations were “unsubstantiated, defamatory, and malicious”.

“These claims are categorically denied in their entirety and are unequivocally rejected as false, reckless, and engineered to tarnish the reputation of both our client and the institution.”

He said the allegations regarding the illegal building activity were “devoid of truth” and “constitute a deliberate campaign to damage IPSA’s standing as a respected educational institution”.

“The insinuation that IPSA or Mr Nazier Osman engaged in unlawful construction practices is rejected. IPSA has consistently acted in good faith and is cooperating fully with the City of Cape Town’s inquiries. Any suggestion [of] … non-compliance or negligence is vehemently denied. We are currently reviewing the matter, and a comprehensive response will be furnished in due course.”

He said the company would submit its detailed response to the allegations by 16 May, but had not responded to the M&G’s follow-up email requesting this further comment by the time of publication.