5 Jul, 2025 | Admin | No Comments

Lesotho Highlands Water Project: Centre local voices in the climate change, conflict and peacebuilding nexus

The rise of conflicts in societies has been attributed to a multitude of factors ranging from political, socio-economic grievances to ethnic and religious hostilities. Poverty, land and food insecurity are worsened by conflict and climate change.

What seems to be missing in the discourse is the interplay between climate, conflict and peace. The rise of resource conflicts, increasing climate-related security risks and the process to foster peace by resolving conflict in nonviolent ways demonstrate that climate change and peacebuilding are interconnected. But there is a tendency to deal with climate change and peacebuilding at high level decision-making structures led by governments and international actors such as the United Nations, marginalising those affected by climate change and conflict, thus failing to sustain peace in local communities.

Top-down approaches to peacebuilding apply universal approaches and local contexts and perspectives are either not acknowledged or neglected in conflict-affected societies. Because local communities disproportionately experience water scarcity, land disputes, livelihood disruptions, climate-induced displacements, the influence of climate change on conflict is more pronounced at local levels compared to national and international levels.

These issues highlight the need to explore how climate change is reshaping the concept of peace at the local level and how such changes can be integrated into peacebuilding efforts. Local practices and approaches to conflict resolution such as community-led dialogue and local adaptation strategies should be strengthened to help mitigate the risks of climate-related conflicts while promoting local ownership and sustainable peace.

The local turn legitimises local norms of building peace and mitigates the effects of climate change, empowers ecologically aligned ontologies and environmentally sustainable practices in many communities while rethinking our understanding of conflict, peace and the causes and consequences of climate change.

The Lesotho Highlands Water Project case

The Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP), established by the 1986 treaty signed by the governments of Lesotho and South Africa, is a multi-phased project that generates hydroelectricity through a system of several large dams and tunnels in Lesotho for domestic use and supplies water to the Vaal River System in South Africa for its economic hub, Gauteng.

The LHWP is often hailed as a model for transboundary water management. Yet beneath this success story lies a complex web of power asymmetries, governance challenges and contested development narratives.

The LHWP has had severe effects on the livelihoods and socioeconomic standing of local people, neglecting to compensate those affected by financial and ecological expenses associated with dams, tunnels and power plants. The stability of the LHWP is threatened by climate change due to the system of river flows feeding into the dams. Increased intensity of rainfall can lead to soil erosion and sedimentation in dams, decreasing water quality and reservoir capacity. These environmental changes pose risks not only to the water supply but also to downstream ecosystems and local agricultural productivity.

As Phase II is under way, a construction company had to suspend operations because acidic and oily wastewater was dumped in rivers and the Katse reservoir, while the wastewater was discharged near the Polihali Dam where animals drink water and women do laundry at the Sekoai River.

People often express frustration over limited participation in decision-making processes, leading to feelings of exclusion and mistrust. Local populations possess local knowledge related to land, water and weather patterns, using their own forecasting methods, crop diversification and soil conservation techniques to cope with climatic variability. Integrating this knowledge with scientific data can enhance climate resilience.

Environmental degradation and political, economic and social instability form a complex and reinforcing cycle that affects local communities. In Lesotho, competition over water and land use has led to disputes between people affected by resettlement and those adjacent to project areas. Displacement has disrupted social fabrics, creating grievances that can escalate into conflict if unaddressed.

Traditional conflict resolution mechanisms remain vital in Lesotho. Chiefs, elders and community councils mediate disputes arising from resource use and projects. These customary processes emphasise consensus-building and restoration of social harmony. But the integration of these local mechanisms with LHWP governance is limited.

Strengthening participatory decision-making and recognising local institutions in project planning could reduce conflicts and increase legitimacy.

Water scarcity driven by climate change heightens competition among people and sectors, exacerbating social tensions. Political dynamics also influence how water stress is managed. Unequal power relations, weak governance and lack of transparent resource allocation can deepen grievances.

Enhancing transparency, accountability and multi-level coordination is crucial. Policies must ensure equitable distribution of benefits and risks, recognise local rights and foster adaptive management responsive to climate variability.

Kgomotso Komane is a PhD candidate and writes on behalf of ESI Project Earth at the University of Pretoria.

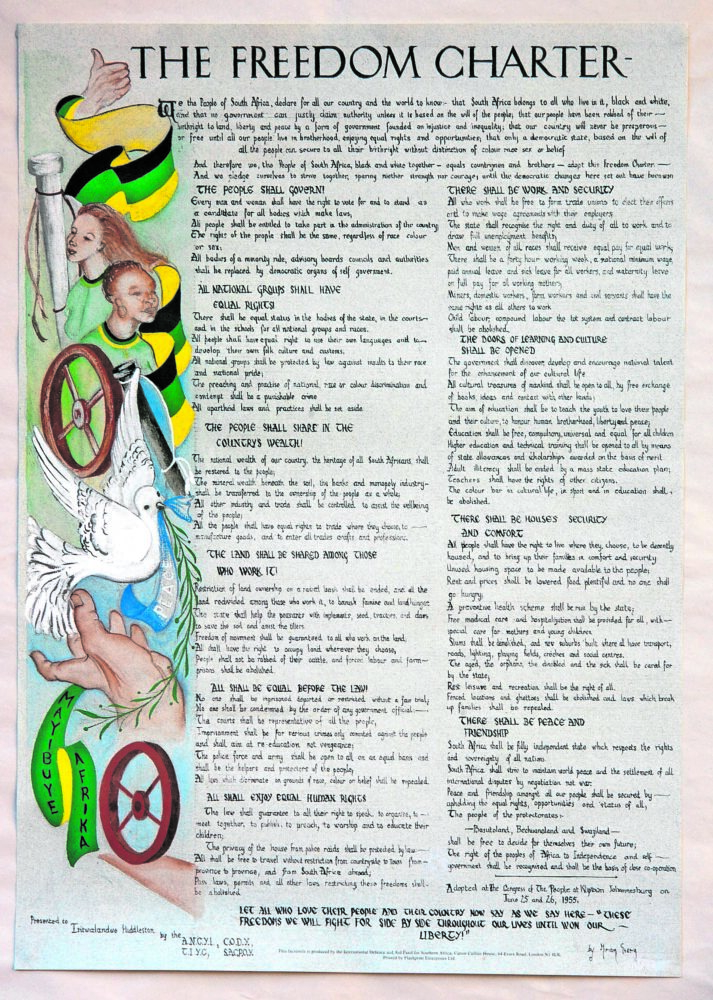

The Freedom Charter was adopted in Kliptown 70 years ago, on 26 June 1955. Thousands of delegates travelled across South Africa — by train, by bus, on foot — to take part in the Congress of the People. They met under an open sky, gathered on a dusty field where a wooden stage had been erected. Armed police watched from the perimeter but the atmosphere was determined and jubilant.

One by one, the clauses of the Charter — on land, work, education, housing, democracy, peace — were read aloud, and each was met with unanimous approval. The charter distilled months of discussion and collective vision.

Discussions of the charter seldom place it in its full historical context. Yet to understand its true significance, we must see it as part of a wider global moment — an era in which oppressed peoples across the world were rising against colonialism.

After the defeat of fascism in 1945, there was a deep sense of possibility. The victory fuelled a new international moral order, embodied in the founding of the United Nations and its charter, with its emphasis on human rights, self-determination and peace. In the colonised world, this sparked a wave of anti-colonial struggle and growing demands for independence. India gained independence in 1947, China, through force of arms, in 1949 and Ghana in 1957.

In April 1955, two months before the Freedom Charter was adopted, 29 newly independent and colonised nations met in Bandung, Indonesia. The Bandung Conference gave voice to the aspirations of the Global South — to end colonialism and racial domination, assert autonomy in world affairs and build cooperation among formerly colonised peoples. Bandung thrilled anti-colonial forces globally. The Freedom Charter emerged amid this excitement.

This hopeful period was shadowed by a fierce imperial backlash. In Iran, prime minister Mohammad Mossadegh’s nationalisation of oil in 1951 was met with a CIA- and MI6-backed coup in 1953. In Guatemala, president Jacobo Árbenz’s land reforms provoked a similar response, and in 1954 the CIA orchestrated his removal.

Around the world, popular sovereignty was crushed to preserve imperial power. The Korean War (1950–53) marked the aggressive militarisation of the Cold War. In January 1961, Congo’s first elected leader, Patrice Lumumba, was assassinated with the support of the CIA. In April that year the CIA organised the failed Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba. In 1965, the US began a full-scale invasion of Vietnam. In 1966, Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah was overthrown in a Western-backed coup.

In South Africa, the vision set out in the Freedom Charter was swiftly met with state repression. Months after its adoption, 156 leaders of the Congress Alliance were arrested and charged with treason. Then came the Sharpeville Massacre in March 1960. The apartheid regime banned the liberation movements underground and, in response, the ANC took the decision to turn to armed struggle.

The Freedom Charter cannot be separated from the process that gave it life — a process that was profoundly democratic and rooted in the daily lives of people. In 1953, the ANC and its partners in the Congress Alliance issued a call for a national dialogue: to ask, plainly and urgently, “What kind of South Africa do we want to live in?”

The response was remarkable. Across the country, in townships, villages, workplaces, churches and at all kinds of gatherings, people came together to develop their demands. Submissions arrived handwritten, typed or dictated to organisers.

The charter expressed a vision of South Africa grounded in equality, justice and shared prosperity. “The people shall govern” affirmed not only the right to vote, but the principle that power must reside with the people. “The land shall be shared among those who work it” challenged the dispossession at the heart of colonial and apartheid rule. Crucially, the charter called for an economy based on public benefit rather than private profit: “The national wealth of our country, the heritage of South Africans, shall be restored to the people.”

Education, housing and healthcare were to be universal and equal. The charter envisioned a South Africa without racism or sexism, where all would be “equal before the law”, with “peace and friendship” pursued abroad.

After the banning of the liberation movements in the 1960s and the brutal repression that followed, the Freedom Charter did not disappear — but it receded from popular memory.

In the 1980s, it surged back into public life with renewed force. The formation of the United Democratic Front in 1983 in Cape Town, and the emergence of the Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu) in 1985 in Durban, gave new organisational life to the charter. Grassroots formations drew on unions, civics and faith groups to take the charter out of the archives and the underground and into the streets. For the powerful mass movement organised in workplaces and communities the charter promised a future grounded in radical democracy and a fundamental redistribution of land and wealth.

The charter became a vital reference point for the negotiations that began after the unbanning of the liberation movements. Its language and principles profoundly shaped elements of the new Constitution.

The charter’s insistence that “South Africa belongs to all who live in it” and that “the people shall govern” was carried through into the constitutional affirmation of non-racialism and universal suffrage. Guarantees of equal rights, human dignity and socio-economic rights such as housing, education and healthcare echo the charter’s vision.

But the transition involved compromise. In the 1980s, the charter had been a call for deep structural transformation. At the settlement, key clauses — particularly those calling for the redistribution of land and the sharing of national wealth — were softened or deferred. The final settlement preserved existing patterns of private property and accepted a macroeconomic framework shaped in part by global neoliberal pressures. While the vote was won, the deeper transformations envisioned in the charter were postponed.

The result is that today, 31 years after the end of apartheid, structural inequalities and mass impoverishment remain. The charter’s economic promises have not been fulfilled.

The 2024 general election marked a historic turning point. Taken together, the two dominant parties garnered support from less than a quarter of the eligible population. Nearly 60% of eligible voters did not participate.

The charter’s promise that “the people shall govern” demands more than a vote — it requires sustained participation. This requires rebuilding mass democratic participation from below. It means rekindling the culture of popular meetings, community mandates and worker-led initiatives that grounded the charter in lived experience. It means going beyond elections and restoring a sense of everyday democratic agency — in schools, workplaces and communities. It means making good on the promise to redistribute land and wealth.

It also means rebuilding solidarity across the Global South. South Africa played a leading role in the formation of the Hague Group in January this year to build an alliance in support of Palestine. This was a major breakthrough that echoed the spirit of Bandung. The meeting that the group will hold in Bogota in July promises to significantly expand its reach and power.

We must recognise the scale of resistance to transformation, both internationally and at home. The criminal attack on Iran by Israel and the United States exposes the brutality of imperial power — and the urgent need for a global counterweight.

In South Africa economic elites and NGOs, think tanks and media projects funded by Western donors often work to frame redistributive politics as illegitimate or reckless. These networks have grown bolder as ANC support has declined.

In June 2023, the Brenthurst Foundation — funded by the Oppenheimer family — convened a conference in Gdansk, Poland. Branded as a summit to “promote democracy”, the conference issued a “Gdansk Declaration” widely read as an attempt to legitimise Western-backed opposition to redistributive politics in the Global South. The Democratic Alliance and the Inkatha Freedom Party were present, along with former Daily Maverick editor Branko Brkic and representatives of Renamo (Mozambique) and Unita (Angola), both reactionary movements that were backed by the West to violently oppose national liberation movements.

The event marked the open emergence of a transnational alliance aimed at neutralising any attempt to challenge elite power in the name of justice or equality.

It is a reminder that the struggle to realise the Freedom Charter’s vision will not be won on moral terms alone. It will require effective political organisation, ideological clarity and courage. The charter was born of struggle. It must now be defended and renewed through struggle.

Ronnie Kasrils is a veteran of the anti-apartheid struggle, and South Africa’s former minister for intelligence services, activist and author.

5 Jul, 2025 | Admin | No Comments

Public private partnerships can help close Africa’s infrastructure deficit

There is a consensus that Africa can increase economic growth by making significant investments in connecting infrastructure — the physical and digital networks that connect towns, cities and countries, enabling seamless trade and data exchange. This includes transport, communication, energy, as well as water and sanitation, which are vital for the free flow of people, goods and services.

When this infrastructure operates optimally it facilitates increased trade, communication, commerce and social development — critical pillars in the objectives of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).

The Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) in 2023 stated that the Africa infrastructure deficit reduced continental economic growth by 2% annually and reduced productivity by 40%, an alarming state of affairs. To address this infrastructure deficit, the Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (Pida), an African Union initiative, produced the Pida Priority Action Plan (2021-2030) with the support of the United Nations. The plan has a critical list of 69 infrastructure projects to be developed in Africa for about $160 billion. Intra-Africa trade is extremely low at only 15%, compared with 68% in Europe and 59% in Asia. According to the ECA, once fully implemented, the AfCFTA aims to increase intra-Africa trade to 35% by 2040.

The objective is to not only increase trade volumes but also promote economic diversification away from reliance on commodity exports towards manufacturing and value-added industries. The changes in the global trade architecture, tariff regimes, aid cancellation, shifting political alliances and elevated geopolitical tensions indicate an urgent need for Africans to increasingly rely on other Africans. This means addressing the critical infrastructure deficits and unlocking intra-African trade is the most important task facing Africa today.

Financing connecting infrastructure

The technical White Paper, titled Missing Connection: Unlocking Sustainable Infrastructure Financing in Africa and co-published by the Africa-Europe Foundation and African Union Development Agency – NEPAD for the Finance in Common Summit held in Cape Town, South Africa in February 2025, noted the continent needs about $150 billion annually in infrastructure investment to address the infrastructure deficit.

Current investment is about $80 billion annually, of which only 40% of this financing comes from governments. About 35% of the financing is from donors and other international partners. The balance of current financing is from the private sector, whose role has taken on increased significance considering the changing donor patterns and decline in China-led financing in recent times. Creating enabling environments for private sector partners to invest in is critical for closing the significant funding gap.

Public private partnerships (PPPs) are increasingly viewed as one infrastructure financing modality that should be increasingly considered by African governments. These partnerships are long-term agreements that involve the granting of specific rights to the private sector to build new infrastructure or undertake substantial renovations of existing infrastructure using private financing and at significant private sector risk. In exchange, the private sector investors are granted long-term concessions over the operations of the assets and are remunerated through user charges, government unitary payments, or a blend of the two where revenue viability gaps exist.

The assets at the end of the partnership contract are transferred to the state and the state has the option to operate the assets or tender out to the private sector for another contract term.

Over the last few years, there has been a huge interest from African governments in using such partnerships to fund their infrastructure deficits. The continent has a low deal flow compared to other regions of the world, but this is set to change if the right policy interventions are applied. McKinsey and Company, in an article titled Solving Africa’s Infrastructure Paradox, noted that although Africa has a large pipeline of projects, for example, the Pida Priority Action Plan initiatives, but on average fewer than 10% of these receive funding.

There are international funds with an appetite to invest in Africa. So why are so few deals being funded? Some of the reasons for the slow conclusion of public private partnership deals in Africa are:

- Feasibility studies or business plans are not undertaken in sufficient detail to assess risks or commercial viability.

- Inadequate enabling legislation, frameworks, and policies tailored for concluding PPP transactions efficiently.

- The inability of governments to issue guarantees because of weak balance sheets or challenges with credit ratings.

- A shortage of skilled public servants who possess the necessary experience to conclude PPP contracts.

- Low liquidity or highly risk averse domestic lenders, thus making foreign lenders the primary option in some markets.

- Currency fluctuations and other political risk factors discourage investment because of the elevated perceived risks.

The African Legal Support Facility (ALSF) based at the African Development Bank undertook a study in 2024 to assess the progress in the development of public private partnership frameworks and supporting legislation. The study, titled Public Private Partnerships, Legal and Institutional Frameworks in Africa: A Comparative Analysis, produced some key findings:

- Out of 54 countries in Africa, 42 have enacted PPP legislation. Out of the 42 countries, 24 have civil law, 13 have common law and five have mixed legal systems.

- Western and Central Africa have the highest percentage of economies that have enacted specific PPP laws, with all countries in the region having laws in place, except for Equatorial Guinea and The Gambia.

- Eastern and Southern Africa have enacted the least specific PPP laws. Among the 12 countries that make up the Southern Africa region, four remain without a specific PPP law: Botswana, eSwatini, Lesotho and South Africa.

- Annual trends showed that the highest rate of enacted laws was from 2015 to 2017 with 16 laws passed over the three years.

- The first African country to enact a specific PPP law was Mauritius in 2004, while the most recent is the Republic of Congo in 2022.

- The restricted tendering method is the most common form of PPP procurement.

South Africa had concluded the most public private partnership deals in Africa as of the end of 2024, raising nearly $5 billion, with Nigeria in second place. South Africa appears to have had better success in PPP deal closure because of an advanced financial market, stable economic policy, favourable legal framework and a perceived transparent procurement process according to various studies.

The country uses Treasury Regulation 16 under the Public Finance Management Act for national and provincial governments and the Municipal PPP Regulation 309 under the Municipal Finance Management Act for local government. These regulations have been undergoing amendments, with Regulation 16 amendments complete and coming into effect on 1 July 2025 and Regulation 309 amendments still need finalisation.

Donor agencies and development finance institutions have directed funding to support the training and institutional building of PPP capabilities in African governments. The Public Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility, a World Bank programme, has successfully implemented institution-building activities to enhance the capacity of government officials around the world. This technical assistance helps to catalyse the adoption of PPP laws, regulations and guidelines in a streamlined manner to facilitate investments.

2025 and beyond

Attracting both domestic and global private sector investors to Africa is a critical part of closing the financing gap and making inroads to closing the infrastructure deficit that prevents Africa from growing at a rate fast enough to create meaningful opportunities, especially for its burgeoning youth population. One of the attractive features of PPPs is the transfer back to the state of the asset at the end of the agreement.

We have seen many privatisations of state-owned enterprises, usually accompanied by opposition from political parties or civil society because of the more permanent transfers of state assets to the ownership and control of the private sector. Governments have raised debt capital in private markets or by tapping into pension funds to fund infrastructure — another at times controversial route because of perceived risks to pensioners of the funds being mismanaged.

Public private partnerships are, however, not a silver bullet to the funding deficit because of the complex nature of the agreements and the real risk of African governments assuming contingent liability exposures inadvertently because of a shortage of skilled bureaucrats. It is incumbent upon our governments to develop the necessary legal frameworks and innovative de-risking mechanisms that will allow the successful conclusion of private sector investments.

Dr Mthandazo Ngwenya is a managing director at Bigen Africa Group and has also served as Africa director of Intellecap Advisory Services.

5 Jul, 2025 | Admin | No Comments

Sparrow-weaver nests help shape bird biodiversity in the southern Kalahari

Conducting fieldwork under the blistering 40ºC heat of the southern Kalahari, Lesedi Moagi had to time her outings to align with the activity of her research subjects — white-browed sparrow-weavers.

“Some mornings, by 7.30am, it was already over 20ºC,” recalled Moagi, a master’s student at the University of Cape Town. “And the birds were already becoming less active. They have to split their daily activities depending on the temperature.”

Moagi’s research focused on understanding how the untidy yet intricate nest structures built by the sparrow-weavers, which live in cooperative family colonies of up to 14 birds, serve as a resource for other bird species in the semi-arid wilderness of the Tswalu Kalahari Reserve.

“We already knew that birds like scaly-feathered weavers, ashy tits and the Acacia pied barbet were roosting in these nests,” she said, noting this behaviour hadn’t been studied in detail.

The inspiration for the research came from another desert species — the sociable weaver — whose apartment-block-like communal nests are used by a variety of species. That research is well-established, Moagi said.

“With white-browed sparrow-weavers, their nests are also being used by other bird species but this has not been studied deeply and it hasn’t been understood as well. That’s how the idea came about — that it would be cool to actually try to understand the value that these nests hold in the ecosystem.”

To assess the effect of the sparrow-weaver’s nest structures, she observed both naturally occurring nests and those that had fallen in the wind, which she relocated to trees without nests. She then compared bird abundance and species diversity in areas with and without nests.

“We wanted to see if they also affect the overall avian community in the Kalahari to see in an area with more of these nests,” she said. “We wanted to measure the avian abundance and the number of species that are actually hanging around these nests. We saw their numbers increasing.”

Her findings position the sparrow-weavers as ecosystem engineers — species that modify the environment in ways that benefit other organisms. But the sparrow-weaver population itself may be under threat.

Once common across the Kalahari, their numbers are declining in some areas. The causes are still unclear and could be linked to changes in rainfall patterns, food availability or habitat changes and need further study, she said.

Moagi said fewer sparrow-weavers could mean fewer shelters, which might force other species to expend more energy building their own, or even struggle to survive.

“The physical changes the sparrow-weavers make influence the distribution of the animals. If we have less of these sparrow-weavers, it might affect the number of the species that are using these structures; it might influence their distribution and their movement.”

The ability to find safe, insulated shelter is critical for survival in the harsh Kalahari environment. “The Kalahari is so hot. Birds can’t finish building a nest in a single day because it gets so hot and they need to conserve their energy.”

Moagi also placed temperature loggers inside and outside the nests to measure their insulation. The results showed that the nests provided a consistent buffer against extreme temperatures — up to a 4ºC difference compared to the surrounding air.

In the Kalahari, that kind of thermal stability is crucial.

With climate change making the Kalahari hotter and drier, such shelter could become even more vital for desert-adapted birds. Protecting the sparrow-weaver and its nesting habitat is crucial, Moagi said, not just for the species itself, but for the broader bird community.

She suggested practical interventions including providing water points and shaded areas in key nesting zones and preserving grasses used in nest-building.

5 Jul, 2025 | Admin | No Comments

The Durban July: The good, the bad and the ugly of Africa’s grandest gallop

Each year on the first Saturday of July, South Africa’s most anticipated sporting and social spectacle gallops into the spotlight — a cultural jamboree known simply as the Durban July. Over time, the event has become more than just a horse race; it is a mirror of the nation’s aspirations, divisions and contradictions.

At its best, the Durban July is a dazzling display of high fashion, high stakes and high society — a multiracial carnival of couture, culture and class. It injects more than R150 million into the local economy and boosts jobs in fashion, hospitality and entertainment.

Rich history resides at this racetrack: from its past to democratic turf, the Greyville Racecourse, framed by the Warwick Triangle, Block AK and Berea, once stood as a symbol of colonial and apartheid exclusion.

Born under the shadow of Royal Ascot in the 1920s, the racecourse became a bastion of racial segregation by the 1940s.

The city’s Indians — many of whom are passionate punters — can today revel in the fact that one of its own, business person Sadha Naidoo, is the chair of Gold Circle Horse Racing and Gambling; he’s the chief steward who will present the main race prize to the winning owner and jockey.

Yet beneath the glitz and glamour lies a more complex narrative: one of exclusion, excess and inequality. The juxtaposition is jarring — luxury marquees with people sipping champagne stand a few metres from working-class punters lining the fences. The People’s Race, as it’s sometimes called, still plays out on unequal terrain.

The July is also where political theatre occasionally steals the show. In 2009, the infamous “Zuma Whisky Incident” saw a glass of whisky flung at the then-president Jacob Zuma — a moment of silent protest and defiance at a highly choreographed elite gathering. It was a symbolic rupture, revealing how political tensions can spill into supposedly apolitical spaces.

Concerns about safety, exploitation and unruly behaviour persist. From petty theft to gender-based harassment, the dark underbelly of the event often escapes the headlines.

Traffic congestion paralyses Durban’s inner-city, while residents complain of noise, gridlock, poor policing and the after-party blasts of music. For many locals, the event is more disruption than delight.

Yet the heart of the July beats far from the parade ring. It begins at dawn in Summerveld, as the elite racehorses undergo their final gallops — sleek, muscled athletes rehearsing for glory in the misty paddocks of KwaZulu-Natal’s misty hill country. Then begins their journey, meticulously choreographed, to Greyville Racecourse, where logistics meet legacy.

Greyville comes alive as the equine stars are welcomed into their stables. In the parade ring, amid the swish of silks, jockeys and horses find a fleeting moment of communion. Then comes the grand gallop — a thunderous sprint of colour and courage, speed and spectacle.

The July is also a kaleidoscope of identity: Zulu regalia, Indian couture, township streetwear and European luxury brands all jostle for attention. It’s an unofficial runway for the rainbow nation — though some ask whose culture is truly being showcased, and who ultimately profits.

Behind the scenes, deals are struck and alliances forged. Boardroom barons and powerbrokers rub shoulders in VIP lounges, while influencers race to out-dress each other in branded content disguised as lifestyle. Once mainly about horses, the race has been overtaken by a battlefield of brands.

There is also a spectre of race, power and representation: despite its rainbow nation feel, questions persist about ownership and access. Who controls the horse racing industry? Whose culture is being showcased? Who profits?

Hollywoodbets is the third most prominent sponsor on the heels of longstanding underwriters Rothmans, until then health minister Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma snuffed it out of the sport of kings with the ban on tobacco, and followed by cellular phone giant Vodacom, until the silent grandstands of Covid-19 lockdown scratched it out.

Hollywoodbets, a sportsbook and betting operator became the title sponsor of the Durban July in 2020. Its purple branding now dominates the racecourse and the broader July experience.

Founded in Durban and rooted in the local racing industry, Hollywoodbets has grown from a modest operation into an international gaming giant with interests in sports betting, horse racing, online casino gaming and community development.

“This year’s Hollywoodbets Durban July is more than just a race,” said spokesperson Zandile Dlamini.

“It’s a full cultural experience. We’re thrilled to offer a lineup that celebrates South African music, lifestyle and diversity. Our goal is to create unforgettable moments for all who attend.”

Raceday is a showpiece of alcohol, excess, extravagance and exploitation — often enabled by the blurred lines of luxury and liberty.

Still, the July remains a symbolic stage for the city and the country. Its contradictions mirror our own: dazzling yet divided, aspirational yet uneven. If managed with vision and fairness, it could be a true platform for transformation — not only for racing but for South African society.

Much of the event’s sustainability now rests on leadership. Naidoo is widely respected for his strategic vision and transformation efforts. Under his stewardship, Gold Circle has navigated post-Covid problems and adapted to an evolving entertainment and betting landscape.

As millions of rands will be splurged, the biggest buzz surrounds the main race, which features 18 runners, with two reserve horses on standby in case of any late scratching.

This Grade 1 contest will be run over 2 200 metres. The favourite is Eight On Eighteen, currently leading the betting market at 14/10 odds. Drawn at gate 11, the colt will be ridden by champion jockey Richard Fourie and is trained by Justin Snaith.

As Durban catches its breath after another unforgettable edition on Saturday, 5 July, one thing is clear: the Durban July remains a metaphor for South Africa. What we choose to see — glamour or grit, triumph or tension — depends on how close we’re willing to look.

Here’s a personal tip: don’t lose your shirt, don’t drink and drive, and catch an Uber home safely.

Marlan Padayachee is a former political, foreign and diplomatic correspondent in the transition from apartheid to democracy and is now a freelance journalist, photographer and researcher.

I have not been able to watch a single match of the football Club World Cup. I have glanced a bit at some games or caught up with the scores on social media.

It is not just the crass commercialism of the enterprise. While the world cup has been taking place in the United States, the self-styled “home of the brave and land of the free”, the US’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency has been staking out parking lots at malls and court houses and rounding up anyone who they think looks like an immigrant.

There are reports of citizens, or those who have applied and are waiting for asylum, being arrested. Students who have participated in the Gaza anti-genocide protests have been labelled as terrorists and a danger to the US government. In this time, the US government agreed with the Israeli government’s unprovoked bombing of Iran and called it self-defence. The US government itself conducted a midnight bombing of Iranian nuclear energy sites, claiming that they were weapon sites.

And what has now become normal is Israel, with the approval of the US, continuing to kill and shoot at Palestinians in Gaza who are scrounging for food and water. The world does not bat an eye when it is reported that a 100 people have been killed in Gaza in a day.

Yet there has not been a single protest or even a measly statement by Fifa officials, club owners or football players against the US government’s destructive actions. Players have been known to take off their shirts, revealing happy birthday messages to loved ones or their religious commitment, but not one of them have had the courage to exclaim support for the people who are the racist targets of ICE or the people of Palestine. I wonder if the Club World Cup will have a 1936 Berlin Olympics Jesse Owens moment? Owens’ success in the sprints and long jump disciplines famously trashed Hitler’s racist Nazi philosophy.

But people are notoriously, deliciously dialectical and contradictory. If the football pitch, albeit overwhelmingly composed of people from working class backgrounds and so-called people of colour, cannot provide the inspiration to dare dream of an equal and better world, free from racism, poverty and inequality, then it will burst out elsewhere.

In New York City, in the Democrat Party primary for mayoral candidates, the world was reminded that it is not a crime or naïve to believe in a better world. Zohran Mamdani defeated Andrew Cuomo, the former governor of New York. Cuomo and his family are regarded as Democrat royalty, and usually that would be enough to ensure he secured the nomination of the party. Cuomo was backed by Democrat aficionados like Bill Clinton, the mainstream media, as well as the billionaires in New York.

New York billionaires, such as Bill Ackman and former New York mayor Mike Bloomberg, together with other billionaires who had supported America’s right-wing president, Donald Trump, pumped about $25 million into Cuomo’s campaign to fight Mamdani. This is the largest Super PAC (Political Action Committee) in New York City mayoral campaign history.

The election for the mayoral position is scheduled to take place in November this year. Cuomo is ambivalent about whether he will run as an independent. Eric Adams, the incumbent mayor, who famously jumped from being Democrat leaning to Trump as stories emerged of his alleged corruption, is expected to be Mamdani’s main rival — although there are whispers of Ackman running, as opposed to supporting another candidate.

Mamdani is only 33 years old, and has been serving as a member of the New York state assembly since 2020. Previously he was a university student. His only work experience besides being a politician, has been a housing counsellor and an attempt to be a hip-hop rapper.

But Mamdani also represents being a global citizen, with cultural influences from all over the world. Zohran, like his father, Ugandan-American academic Mahmoud Mamdani, author of Good Muslim, Bad Muslim, was born in Uganda. He lived there until he was seven years old, when they relocated to New York. He also stayed with his father in Cape Town in the late 1990s. His father had a famous fight with the University of Cape Town when he pushed for a radical change in curriculum to one that is decolonised and African-centred.

Zohran Mamdani is an immigrant. Besides his cultural roots in East and Southern Africa, his mother is Mira Nair, the Indian-American filmmaker. Her body of work includes Mississippi Masala starring Denzel Washington and the critically acclaimed Salaam Bombay. He is linked to the urbane inner city culture of Uganda and the US, with his hip-hop rap career. His mother’s roots are in South India, and therefore her cultural religious background is Hindu, whereas his father is of Islamic origin. He is African, Asian, American and, with the British colonialism of both Uganda and South Africa, we could even say he is also European.

Mamdani’s central message to New Yorkers was that it was his stated objective to make New York affordable for all New Yorkers, especially the working and middle classes. New York is the most expensive city to live in the US. He describes himself as a democratic socialist, exclaiming that he is inspired by the words of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr, who said: “Call it democracy, or call it democratic socialism, but there must be a better distribution of wealth within this country”. He also quotes King saying: “What good is having the right to sit at a lunch counter, if you can’t afford to buy a hamburger?”

Mamdani promised that, if elected, he would freeze rents for at least two million tenants, and would make certain bus routes have faster buses that are also free. He would provide universal day care for all New Yorkers. And he would pilot at least one government-owned grocery store in each of the five New York boroughs. He promised as well to employ social workers and counsellors to assist New Yorkers with mental health issues. Currently, the police are expected to help New Yorkers who mentally break down.

In the past Mamdani has publicly supported the Palestinian struggle, and he maintained that message throughout the campaign. He has called the 7 October attack by Hamas a war crime because it targeted civilians.

His campaign was not based on expensive television and radio commercials. Rather, he met everyone, personally walking the entire length of the city. Besides getting donations from the average New Yorker, his campaign also attracted 47 000 volunteers, who knocked on nearly every New Yorker’s door.

After his stunning victory over Cuomo, countless mainstream and social media commentators started to speculate whether his campaign will have a direct effect on how the Democrat Party positions itself. Much has been made of his age and that young people, especially those who did not vote before, supported Mamdani. We can expect that the media and consultant talking heads will make it seem that it’s his age, embracing of social media as the reason for his success, and harping on about his cultural identity — first Muslim, first South Asian and so forth.

This is a deflection. It is a continuation of the dumbing down of political activism. It seeks to make politics and who we support as theatre and entertainment, with savvy marketing gimmicks. Please do not fall for it.

The reason for Mamdani’s appeal, even for Jewish people who knew of his support for the Palestinian struggle, is because of its authenticity; a genuine commitment to stand up to and deal with the daily struggles of the people. It is unafraid to be progressive and seeks no approval from the elite.

I hope the elite in South African politics are taking note. It is not about filling stadiums or glossy election manifestos. Or the numbers of views on TikTok and YouTube, but a believable commitment to a progressive agenda. Mirror Zohran Mamdani. Create a practical programme based on making life more affordable for the majority of South Africans. Let these programmes be your centre, not an opportunistic economic transformation programme that mainly revolves around lining your pocket and those of your friends.

In the South, many of us are playing political football in parliament and government, whereas outside of the political industry, people are being killed and maimed, and are starving and traumatised, just hoping that someone of note will join them in the struggle for a better South, better Africa and better world.

Donovan E Williams is a social commentator. @TheSherpaZA on X.

A defence witness told a judicial tribunal on Thursday that emojis exchanged in WhatsApp messages between Eastern Cape Judge President Selby Mbenenge and a junior legal professional were consistent with casual conversation, challenging claims that they were used to sexually harass her.

Information and communications technology expert Vincent Mello testified that the messages — central to a misconduct inquiry against Mbenenge — reflected standard emoji use, citing references from Unicode Consortium and Emojipedia.

His analysis countered previous expert evidence which suggested the symbols were deployed with sexualised intent.

Mello was called by Mbenenge’s legal team to analyse disputed WhatsApp messages between the judge president and legal professional Andiswa Mengo, who has accused him of sending inappropriate messages of a sexual nature over WhatsApp.

During the second sitting in May, linguistics specialist Zakeera Docrat testified that emojis had been used for non-standard purposes to depict sexual acts and as a means to sexually harass.

Mello told the tribunal that his interpretation revealed the contrary and said his findings relied on the Unicode Consortium standards and Emojipedia, an online reference site that catalogues emoji definitions. His testimony suggested that the tone of the conversation was casual and mutually light-hearted, inconsistent with allegations of unwanted sexual advances.

This contrasts with Mengo’s own testimony, in which she described persistent late-night messages, requests for photos and a sense of pressure due to Mbenenge’s powerful position. She said his messages were unwanted and inappropriate but she felt unable to challenge him.

Under cross-examination by Mbenenge’s counsel, Griffiths Madonsela, Mello said that in his analysis of the WhatsApp exchanges, he counted 189 emoji used — 97 by Mbenenge and 69 by Mengo.

He told the tribunal that the “rolling on the floor laughing” emoji was used 27 times by Mbenenge and 28 times by Mengo. The “see-no-evil monkey” emoji was used 24 times by Mbenenge and 20 times by Mengo. The “winking face” was used twice by Mbenenge and once by Mengo.

Other emojis in the messages included the “thinking face” and “face with tongue” — both used by Mbenenge — and the “flushed face” and “squinting face with tongue” used by Mengo.

Mello interpreted these emojis as casual and in line with standard use.

He also noted the use of the “peach” and “eggplant” emojis — widely regarded as suggestive symbols for buttocks and male genitalia, respectively — while notable, could not be attributed any specific intent.

Mello further testified that a portion of the WhatsApp messages exchanged between the two — from 22 June to 8 July 2021 — was missing from the record, making the communication incomplete.

He suggested that the missing messages raised questions about the integrity of the evidence.

The WhatsApp messages have been a central feature in the case, which has grappled with interpreting the tone and content of the digital exchanges between Mbenenge and Mengo.

In May, digital forensic analyst François Muller, testified that Mengo had communicated with the judge from two different phones. He confirmed retrieving and restoring data from both devices, which formed the basis of the messages under scrutiny.

However, Mello told the tribunal that he had only examined data extracted from one of the phones — the one provided to him by Mbenenge’s legal team — and not the full set of data Muller had reviewed.

This drew criticism from evidence leader Salome Scheepers, who questioned whether Mello’s opinion was informed by a complete dataset.

Scheepers also challenged Mello’s qualifications, arguing that he lacked the forensic and linguistic expertise necessary to interpret digital evidence, specifically the contextual nuances of emoji use.

In May, Docrat warned that emojis were not neutral symbols and could vary in meaning depending on the recipient’s interpretation, the platform and the interpersonal history between the communicators.

Scheepers drew on Docrat’s earlier testimony to argue that Mello’s approach — which focused on Unicode definitions — was too narrow.

She pressed Mello on the variability of emoji meanings across different devices and social contexts, noting that the same emoji could convey different messages, depending on the relationship between the users.

Scheepers further said some emojis, such as the “see-no-evil monkey”, could be interpreted flirtatiously — an interpretation not captured by standard references nor by Mello’s interpretation.

Mello maintained that his role was technical and not interpretive. He also cast doubt on the authenticity of certain images included in Mengo’s complaint. According to him, the photos she claimed were sent by Mbenenge did not match WhatsApp’s metadata structure.

The tribunal has also heard arguments about CCTV footage allegedly missing from the court building on the date Mengo said she was harassed.

Scheepers confirmed during cross-examination in May that some footage from the relevant day was no longer available, despite requests from the tribunal. The lack of CCTV evidence has further complicated the tribunal’s efforts to establish a definitive timeline of events.

Mengo, who testified earlier in the year, maintained that Mbenenge made sexual advances, sent inappropriate messages and exposed himself to her at the Mthatha high court buildings. Her testimony was supported by screenshots and messages, although she admitted under cross-examination that some conversations had continued beyond the alleged incidents.

The defence has argued that Mengo’s continued engagement with the judge — with light-hearted emojis and informal language — contradicts her claims of persistent harassment. The defence said Mengo had reciprocated with messages that reflected a cordial relationship.

Strengthening the defence’s case, Mbenenge’s witness, former secretary Zintle Nkqayi, testified that the judge was not at work at the time Mengo alleges he exposed himself to her. Nkqayi said Mbenenge had gone to the bank and she had subsequently accompanied him to a lecture and to court.

The tribunal is expected to conclude on 11 July, before which Mbenenge will take the witness stand.

Tens of thousands of horse racing punters, fashionistas, foodies and other visitors who descend on eThekwini to party at the Hollywoodbets Durban July this weekend are expected to contribute around R700 million to the city’s GDP.

Africa’s largest horseracing event, themed Marvels of Mzansi, is expected to generate significant economic activity and create 4 000 jobs, eThekwini Mayor Cyril Xaba said at the launch of the event at Westown Square in Shongweni.

The event takes place at Greyville Racecourse on 5 July.

Xaba said the city’s tourism and hospitality sectors anticipate an 80% hotel occupancy rate as visitors converge for the horseracing and fashion spectacle, which celebrates South Africa’s cultural heritage, diversity and landscapes.

“The direct spend is estimated at R278 million, with a total of R700 million contribution to the eThekwini GDP, and a total number of 4 000 jobs to be created,” Xaba said.

The economic impact will be generated at the racecourse and at side events, including Fact Durban Rocks, Any Given Sunday, Anywhere in the City and Mojo’s July Weekend, across the city.

Xaba said Durban had geared up to ensure visitors’ safety during the events.

“Our law-enforcement agencies have developed an integrated safety plan, supported by the private security industry. Visitors are guaranteed a safe stay in the city with high police visibility, particularly around the Greyville precinct and other strategic sites across the municipality.”

South Africa’s fashion industry, traditionally synonymous with the event, will showcase the work of professional designers and upcoming talent at the Durban July Fashion Experience, a collaboration between the city and the Hollywood Foundation.

Twenty-five designers will present Marvels of Mzansi collections, featuring three categories, including the Young Designers Awards, with 10 student finalists competing for bursaries and a fashion travel package, the Durban Fashion Fair Rising Stars.

Nine emerging designers supported by eThekwini’s Fashion Development Programme will vie for a R250 000 business development prize and the Invited Designer Showcase, which will display the collections of six established designers.

Gold Circle sponsorship and marketing executive Steve Marshall said the event contributed more than R700 million to the city’s GDP in 2024.

“Its impact on racing is undeniable — it’s the most prestigious race in South Africa. It’s got a prize of over R5 million and it’s the race that every trainer, owner, jockey, crew or breeder wants to win. It’s in their dreams,” Marshall said.

Hollywoodbets brand and communications manager Devin Heffer said the event brought together key sectors across the city.

“This race means so much to so many people, not just the racing industry, but everyone is intertwined. All the public, hospitality, tourism, the government, the GDP — everything is affected and infected with July fever,” he said.

Xaba said he was speaking to hospitality stakeholders to enhance visitor experiences and align with future development plans.

The city was investing R600 million annually in bulk infrastructure for catalytic projects, such as the R15 billion Shongweni Development and the R25 billion Sibaya Precinct Development to elevate tourism infrastructure.

“We are also looking into how we can invest more resources including setting aside a budget to improve tourism infrastructure,” Xaba said.

“The Hollywoodbets Durban July is more than a race — it is a catalyst for social cohesion as it unites South Africans through the passion of sport, the expression of cultural pride and the glamour of fashion,” Xaba said.

“We are really looking forward to the 5th of July and we are ready to roll out the red carpet for our visitors because Durban is open for business.”

4 Jul, 2025 | Admin | No Comments

A primer for the White House visit by West and Central African countries

A few months ago, the chairman of the Africa and Global Health Policy Subcommittee of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Senator Ted Cruz, hosted a roundtable discussion that tackled energy and critical mineral partnerships with the ambassadors and representatives of 19 African countries and the AU. Those African countries included Gabon, Mauritania and Senegal.

Now, President Donald Trump is slated to host the heads of state of Gabon, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mauritania and Senegal for a luncheon discussion at the White House. According to a White House official, next week’s event will explore “incredible commercial opportunities which benefit both the American people and our African partners”.

If that is the intent, the visit will provide an extraordinary opportunity for these coastal African countries to unlock tangible benefits from the increased emphasis on expanded trade and private investment in the African affairs of the US government. In parallel, it will provide the Trump administration with a valuable opportunity to demonstrate to the American people that peace, security and prosperity can be better achieved through commerce and investment than through development assistance.

As with any White House visit, the event is not without known downside risks. To mitigate some of those, the invited heads of state should identify and address any serious concerns with bilateral relations held by the Trump administration. They should also arrive with a concrete set of commercial and investment proposals endorsed by the private sector. Otherwise, they could meet the same fate as the recent South African delegation.

Invited Countries

The Trump administration selected a set of African countries with important similarities. One is that all of them are perceived to be of high importance in countering the spread of violent extremism on the African continent. That is because the US government is extremely concerned about the risk of violent extremism spreading into coastal West and Central African countries with low impacts of terrorism (e.g. Gabon, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mauritania and Senegal) from neighboring Sahelean countries with high impacts of terrorism (i.e. Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Mali, Niger, Nigeria).

Another is that none of the invited countries have been designated as having an exceptional lack of reciprocity in their bilateral trade relationships with the US. When the Trump administration recently set reciprocal tariffs, they were not identified as “worst offenders” among US trading partners.

At the same time, the Trump administration has selected a set of African countries with important differences. One is that the majority have diplomatic relations with Israel. However, one does not — Mauritania.

Another is that there is a wide range of military expenditure as a percentage of gross domestic product. At the low end, Liberia spent 0.7% in 2024. At the high end, Mauritania spent 2.2%. That suggests varying commitments to conducting independent operations.

Yet another is that some of the countries appear to meet the stated criteria for the partial suspension of the admission of their citizens to the US. One invitee has been identified as being at risk of becoming a recalcitrant country by the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement — Gabon. One invited country has a higher B1-B2 overstay rate than Burundi — Liberia. And, two invited countries have a higher nonimmigrant students and exchange visitors overstay rate than Burundi — Gabon and Liberia.

That raises important questions about why those countries received invitations, given that the Trump administration recently imposed partial suspension on the admission of citizens from Burundi and Sierra Leone over their overstay rates and/or historical recalcitrance status.

Valuable Opportunities

The White House visit will provide coastal African countries with an exceptional opportunity to expand trade and private investment with the US. The Trump administration has indicated that it is committed to driving economic growth through expanded trade and private investment rather than development assistance.

In response, the US Department of State has made commercial diplomacy a “core focus” in African affairs. US Chiefs of Mission are now being evaluated on their ability to advocate for market reforms identified by the private sector, facilitate new commercial and investment opportunities for US individuals and companies and implement major infrastructure projects that “unlock economic growth and attract private investment”. This focus on “trade not aid” provides the heads of state of Gabon, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mauritania and Senegal with an extraordinary opportunity to pursue prosperity through commerce and investment in their bilateral relations with the US.

At the same time, the White House visit will provide the Trump administration with a timely opportunity to demonstrate that their strategic approach to African affairs is better than the strategic approaches of the Biden and Obama administrations. That will require proof points. The Trump administration will need to show that it actually has delivered on its promise to increase the prosperity of Americans through African affairs.

Such proof points might include cases of new market expansion for US companies, new US investments by Africans and new reforms in African markets demanded by the private sector. In the process, the Trump administration will be looking for proof points that reinforce other whole-of-government priorities. Examples could include higher use of US maritime industries, expanded access to critical mineral resources, increased exports of American coal, liquid natural gas and associated energy generation technologies and improved capacity of African partners to conduct independent military operations. Those could be controversial but they are entirely consistent with what Trump promised American voters throughout his recent presidential campaign.

Good Preparation

The recent White House visit by President Cyril Ramaphosa serves as a warning to the invited heads of state. To mitigate against a similar confrontation, they should proactively seek to identify and address any serious problems with bilateral relations held by the Trump administration prior to arriving at the White House.

For example, they should seek to identify and address any immigration and travel-related concerns that the administration might have about overstay rates, information-sharing cooperation, identity-management procedures, public safety risks and terrorism-related risks. That includes anti-semitism concerns. They should seek to identify and address any unfair exploitation concerns that the administration might have about the fines, practices, policies and taxes that their government levies on American companies.

And, they should seek to identify and address any strategic competition concerns that the Trump administration might have about their relations with US adversaries and rivals (e.g. China, Iran, Venezuela). That includes proliferation and sanctions-busting concerns. If they can take those concerns off the table, they will create more room for laying down the cards on commercial and investment deals.

To be clear, that is not the only lesson to be learned from the South African visit. Another is that it is critical for African heads of state to arrive at the White House with a concrete set of commercial and investment proposals that have the endorsement of US companies and investors.

President Trump does not invite African heads of state over to talk about golf. He wants to deliver on his campaign commitments to the American people. Moreover, he wants to deliver on those commitments prior to the midterm elections. It is therefore imperative that the invited heads of state not only build rapport, ask smart questions and make smart tradeoffs during their luncheon discussion. They should seek to jumpstart and anchor the deal-making process by putting an initial set of multiple equivalent proposals simultaneously on the table.

That will signal to Trump that their governments are willing and able to strike big commercial and investment deals with the US. Unfortunately, the South African delegation failed to go down that path. It is therefore not surprising that their visit failed to significantly improve the prosperity of either Americans or South Africans.

Michael Walsh is a senior fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute.

1 Jul, 2025 | Admin | No Comments

WNBA players rank Caitlin Clark 9th best All-Star guard despite leading fan voting

The WNBA announced the remaining eight starters for the 2025 All-Star Game after it was revealed Indiana Fever star Caitlin Clark and Minnesota Lynx leader Napheesa Collier will be this year’s captains.

While looking over the overall scores following the voting process, Clark’s position among her peers seemed surprising.

There are three voting groups for the WNBA All-Star process: fan rank, media rank and player rank for the guards and frontcourt players. While Clark was first in fan votes, and third among the media, her fellow WNBA players ranked her ninth among the guards.

CLICK HERE FOR MORE SPORTS COVERAGE ON FOXNEWS.COM

Clark finished second among all players largely because fan votes account for 50% of the votes to determine starters. But it was Dallas Wings rookie Paige Bueckers, the No. 1 overall pick in the WNBA Draft earlier this year, taking the top spot after finishing second in fan rank, fifth in media rank and fourth in player rank among the guards.

The Atlanta Dream’s Allisha Gray, one of the WNBA All-Star starters, finished first in media rank and player rank, while players like Seattle’s Skylar Diggins, New York’s Sabrina Ionescu and Natasha Cloud, Washington’s Brittney Sykes and more finished above Clark in terms of player rank.

Perhaps a main reason why Clark’s peers ranked her so low among guards is due to playing only nine of the Fever’s 16 games this season. Clark has been dealing with injuries in her sophomore season, which continues now as she’s missed the last two games.

Clark had been struggling lately as well, going just 13-of-47 from three-point territory in her last three games.

Still, Clark is averaging 18.2 points, 8.9 assists, five rebounds and 1.6 steals over 33.3 minutes per game this season. Only the Phoenix Mercury’s Alyssa Thomas — who could be among the 12 All-Star Game reserves, which will be selected by the league’s head coaches and announced this Sunday — has more assists per game (9.3), and she’s touched the hardwood in 12 contests this season.

Clark received 1,293,526 votes from the fans.

While Clark has been integral in the rise of the WNBA’s popularity since breaking rookie and league records last season with the Fever, there have been many contentious moments over that span of games with opponents.

This season, a physical altercation broke out against the Connecticut Sun, during which Clark was hit in the face and shoved to the ground during a play. Later in the game, Clark’s teammate, Sophie Cunningham, retaliated against Sun guard Jacy Sheldon in another scuffle that led to ejections.

And, of course, Clark was the center of national sports conversation after instances against the Sun, Chicago Sky and others.

But Clark and Collier will be the ones drafting players to their All-Star squads, and now they know who will be starting with them at the Gainbridge Fieldhouse, Clark’s Fever home, on July 19.

They will get to choose from the following starters:

The WNBA All-Star Game draft results, which will include the 12 reserve players when head coaches sent their votes in, will be revealed on July 8.

Follow Fox News Digital’s sports coverage on X, and subscribe to the Fox News Sports Huddle newsletter.